What Senate Democrats Blew Up in 2003

The Senate's longstanding strong consensus against partisan filibusters of judicial nominations

With the background of last week’s post on the filibuster and cloture generally, let’s now look at the history of the filibuster and cloture with respect to judicial nominees at the outset of 2003, when Senate Democrats decided to deploy the filibuster against George W. Bush’s nomination of Miguel Estrada to a D.C. Circuit seat.

That history may be summarized in several overlapping propositions:

It was extremely rare even to have a cloture vote on a judicial nomination.

No judicial nomination had ever been defeated by a minority party’s blockage of cloture.

No lower-court judicial nomination had ever been derailed by the failure of a cloture vote.

Leaders of a political party in the Senate had never demanded that party members block cloture on a judicial nomination.

* * *

As we have seen, in 1949 the Senate revised its cloture rule in a way that “by happenstance” extended the rule to cover nominations. Over the more than five decades from that revision until the beginning of 2003, the Senate confirmed more than 2,000 lower-court nominations (2,158 by my tally). As Table 6 of this Congressional Research Service report reflects, the Senate had cloture votes on only eleven lower-court nominations during these 50+ years.

The fact that there were cloture votes on eleven lower-court nominations does not mean that there were filibuster efforts against these eleven nominations. Recall that a cloture vote is not itself evidence of a filibuster effort. Any single senator for any reason may deny the unanimous consent that would be needed to proceed directly to a vote on the nomination itself. When unanimous consent hasn’t been obtained, supporters of a nomination file a cloture motion to put an end to further debate.

How many of these eleven nominations can plausibly be said to have been the target of a genuine filibuster effort? Answering this question calls for the exercise of some judgment. In theory you might say that any time a single senator made a cloture vote necessary in the hope of defeating the nomination, that senator was filibustering the nomination. But when there was no prospect that the cloture vote would be defeated, it trivializes the concept to say that the nomination faced a filibuster.

When we look at the eleven nominations in Table 6, we see that the cloture motions on six of them passed overwhelmingly, with 85 or more yes votes. It would seem clear that they did not face any serious filibuster effort.

A seventh cloture motion, on Bill Clinton’s nomination of Brian Stewart to a federal district court seat in Utah, can be eliminated for a very different reason. As I have detailed in a previous Confirmation Tales post, Stewart was a friend of Senate Judiciary Committee chairman Orrin Hatch, and Hatch raced his nomination through the committee. Senate Democrats defeated the cloture motion on Stewart’s nomination not in order to kill the nomination but rather to protest that it was moving ahead of other pending nominations. The Senate ended up confirming Stewart by a vote of 93 to 5.

That leaves us with four nominations to consider. Let’s run through them in chronological order:

Stephen Breyer, First Circuit, 1980

Stephen Breyer had an extraordinarily expedited confirmation process to his First Circuit seat. Jimmy Carter nominated him to the First Circuit on November 13, 1980—nine days after Ronald Reagan defeated Carter’s bid for re-election and the Republicans won control of the incoming Senate. Senate majority leader Robert Byrd aimed to get Breyer confirmed by the full Senate on December 9, but he was unable to get unanimous consent to proceed to a floor vote, so a cloture motion was filed. The motion obtained 68 yes votes, eight more than it needed. Sixteen Republican senators voted for cloture. Three Democratic senators voted against, and three others didn’t vote—which was the practical equivalent of a vote against. Breyer’s nomination was then confirmed by a vote of 80-10.

Reasonable minds can differ on whether to categorize opposition to the cloture motion on Breyer as a filibuster. On the one hand, opponents were indeed trying to defeat cloture in order to block confirmation. On the other hand, their objection was that the nomination should have been handled in the ordinary manner, not accelerated at rocket speed past many earlier nominations.

If you classify the opposition as a filibuster, two points are worth noting. First, the opposition was led by Democrat Robert Morgan of North Carolina, along with Republican Gordon Humphrey of New Hampshire. Second, there was no concerted Republican effort against cloture. Republican whip Ted Stevens voted for cloture, as did Strom Thurmond, the senior Republican on the Judiciary Committee. (Humphrey, first elected in 1978, was the second most junior Republican.)

J. Harvie Wilkinson, Fourth Circuit, 1984

In 1984, the first cloture motion on Ronald Reagan’s nomination of J. Harvie Wilkinson to the Fourth Circuit fell three votes short of the sixty-vote threshold, amidst arguments by some Democratic senators that further investigation into allegations against Wilkinson was necessary. Wilkinson returned to the Judiciary Committee a week later for a second hearing, and two days after the hearing, a second cloture motion prevailed by a vote of 65 to 32. Eleven Democrats voted for cloture. He was then confirmed by a vote of 58 to 39.

Although one is entitled to be suspicious of claims by senators that a delaying measure is only for the purpose of getting more information, the senators who changed their votes to yes on the second Wilkinson cloture motion validated their claims.

It’s also noteworthy that Wilkinson’s final nomination vote received fewer than 60 votes. Seven senators who voted for cloture voted against confirmation. These senators would have blocked Wilkinson’s confirmation if they had voted against cloture. But in evident opposition to the notion that a judicial nominee should be filibustered, they enabled him to be confirmed even as they voted against his confirmation.

Sidney Fitzwater, Northern District of Texas, 1986

In March 1986, the Senate voted 64 to 33 in favor of cloture on Ronald Reagan’s nomination of Sidney Fitzwater to a federal district judgeship in Texas. Twelve Democrats, including Fitzwater’s home-state senator Lloyd Bentsen, voted in favor of cloture.

The Senate proceeded the same day to confirm Fitzwater’s nomination by a vote of 52 to 42. Eight of the twelve Democrats who voted in favor of cloture voted against Fitzwater’s confirmation. Bentsen was among those eight. Here again, the split vote of these eight Democrats would appear to manifest an opposition to filibustering a judicial nomination.

Edward Carnes, Eleventh Circuit, 1992

In 1992, George H.W. Bush nominated Edward Carnes to an Eleventh Circuit seat in Alabama. In September, the Senate voted for cloture on Carnes’s nomination by a vote of 66 to 30. Twenty-four Democrats, including both Alabama senators, voted for cloture. The same day, the Senate confirmed Carnes’s nomination by a vote of 62 to 36. Four Democrats who voted for cloture voted against confirmation.

One curiosity on Carnes’s nomination is that Democrats controlled the Senate in 1992. So majority leader George Mitchell (who voted against cloture and against confirmation) could have killed the nomination simply by never bringing it to the floor. Why didn’t he? As I will address more fully in a separate post, Senator Richard Shelby of Alabama, who was then a Democrat (he switched parties in 1994), strong-armed his fellow Democrats into giving Carnes a cloture vote. Shelby’s extraordinary maneuver threatened several district-court nominations that Democrats had forced Bush to make, including that of a 37-year-old New York lawyer by the name of Sonia Sotomayor.

* * *

Let’s also consider the three Supreme Court nominations on which cloture votes had taken place before 2003.

Abe Fortas, 1968

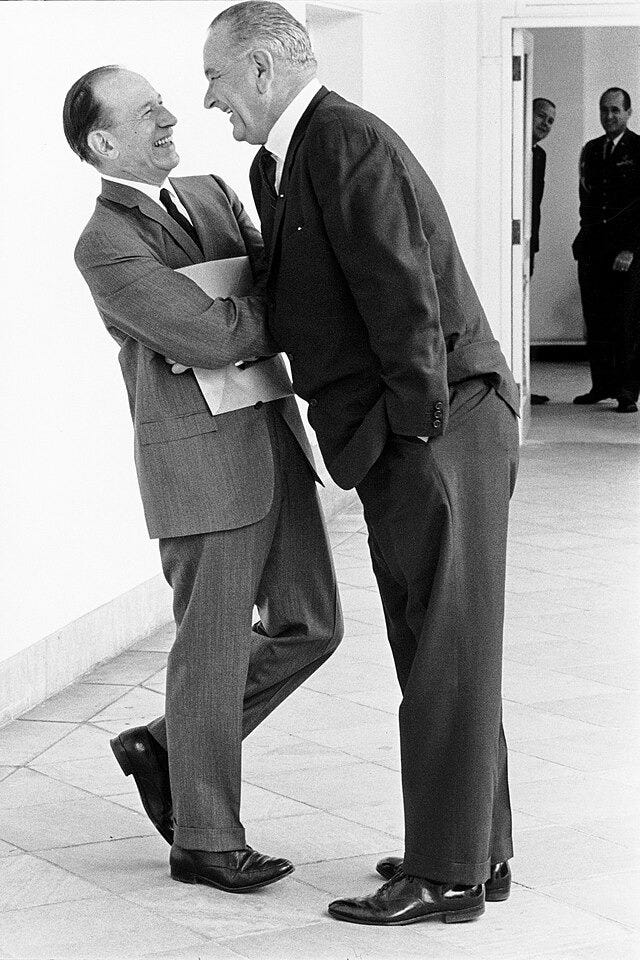

In June 1968, Chief Justice Earl Warren informed Lyndon B. Johnson that he was retiring effective upon the confirmation of his successor. Johnson nominated his crony, Associate Justice Abe Fortas, to be Chief Justice, but bipartisan opposition to Fortas’s nomination quickly developed.

In October, a cloture vote on Fortas’s nomination failed, as it received only 45 votes in support and 43 votes against. Of the 66 Democrats in the Senate, a bare majority — 35 — voted for cloture, 19 voted against, and 12 somehow managed not to be present at the time their leader scheduled the vote. The cloture rule then in effect required the votes of two-thirds of senators present, so the cloture vote fell short by 14 votes. Johnson then withdrew the nomination.

As of 2003, the Fortas nomination was the only judicial nomination ever to be defeated by a filibuster. The filibuster had bipartisan support: 24 Republicans joined with 19 Democrats. It also was far from clear that the Fortas nomination would have garnered the majority needed for confirmation.

William Rehnquist, 1971

Richard M. Nixon nominated William Rehnquist as an associate justice in October 1971. In December, the cloture motion on Rehnquist’s nomination fell a full eleven votes short of passage. It received 52 affirmative votes and 42 negative votes. Under the rule then in effect, it needed to obtain two-thirds of senators voting—63 yes votes.

But despite the defeat of the cloture motion, opponents of Rehnquist’s nomination agreed to a final confirmation vote that same day. Their agreement to forgo their defeat of cloture strongly suggests that they did not want to legitimize the filibuster as a partisan tool.

Remarkably, Rehnquist’s nomination was confirmed by a vote of 68 to 26. He received fewer votes against his confirmation than against cloture.

William Rehnquist, 1986

William Rehnquist also had a cloture vote on Ronald Reagan’s nomination elevating him to be chief justice in 1986. The cloture motion passed by a vote of 68 to 31. Rehnquist was then confirmed by a vote of 65 to 33.

* * *

Perhaps the clearest evidence of the Senate’s strong aversion to filibustering judicial nominees came in 1991, on George H.W. Bush’s nomination of Clarence Thomas to the Supreme Court. I will not attempt to recount here the extraordinary intensity of the hostility to Thomas’s nomination. For present purposes, what is most remarkable is that Thomas’s opponents made no effort to filibuster his nomination. Any single senator could have forced a cloture vote on Thomas’s nomination, but no one did.

The Senate ended up confirming Thomas by a narrow vote of 52 to 48. You might think that the 48 votes against his confirmation meant that there would have been the 41 votes needed to block cloture. But the fact that Thomas’s most strident opponents did not even seek a cloture vote suggests either that they knew they would lose or that they themselves regarded a partisan filibuster as illegitimate.

* * *

In my initial post on Miguel Estrada’s nomination, I stated too loosely that the filibuster was a “weapon that had never before been used against an appellate nominee.” That proposition is contestable, as my discussion of the appellate nominations of Breyer, Wilkinson, and Carnes indicates. What isn’t contestable is that the leadership of a minority party in the Senate had never undertaken to insist that their members block cloture on a judicial nomination.

No lower-court nomination had ever been defeated by a filibuster. Senate Democrats preparing to battle against Miguel Estrada’s nomination were determined to change that.