Senate Democrats Filibuster D.C. Circuit Nominee Miguel Estrada

Dramatic escalation of confirmation wars

Against the backdrop of the Senate’s then-longstanding strong consensus against partisan filibusters of judicial nominations, let’s turn to Senate Democrats’ momentous decision in 2003 to deploy the filibuster against George W. Bush’s nomination of Miguel Estrada to a D.C. Circuit seat.

* * *

Miguel Estrada’s nomination appeared dead in the water after his confirmation hearing on September 26, 2002. Despite (or perhaps because of) his outstanding credentials and the ardent praise he had earned across the ideological spectrum from everyone he had worked with other than one embittered radical ideologue, Democrats on the Judiciary Committee were unified against him, so he would not have the votes to be reported out of committee.

But forty days after his hearing, the elections on November 5 delivered control of the new Senate in 2003 to Republicans by a narrow margin of 51 to 49. So the new Republican majority on the Judiciary Committee, with my old boss Orrin Hatch as chairman, would vote on Estrada’s nomination.

What’s more, a senior Senate staffer tells me, in their campaign events Republicans were surprised how favorably their audiences responded to their mention of the battle over Bush’s judicial nominees. So the new Republican majority would make it a priority to confirm Estrada’s nomination.

* * *

At a retreat in April 2001, Senate Democrats, at the instigation of rookie New York senator Chuck Schumer, had batted about “chang[ing] the ground rules” on opposing judicial nominations. Although they avoided talking about it publicly, what that meant was that they were gearing up to filibuster select nominees. Senator Jim Jeffords’s decision just a few weeks later to leave the Republican party and caucus with the Democrats gave them a majority in the Senate, so they could stymie Bush’s nominees without defeating cloture motions (e.g., by simple inaction). But in 2003, their only way to defeat Estrada’s nomination was by filibustering him.

On January 30, 2003, the Judiciary Committee favorably reported Estrada’s nomination to the Senate floor. On February 5, the Senate began debate on Estrada’s nomination. Over the course of the next month, that debate took nearly 100 hours of floor time. On seventeen separate occasions, new majority leader Bill Frist sought unanimous consent to bring the nomination to a vote. On all seventeen occasions, his request for consent was denied. On March 4, supporters of Estrada’s nomination filed a cloture motion to bring debate to an end.

On March 6, that cloture motion failed, as it received only 55 of the 60 votes needed for passage. All 51 Republican senators voting yea were joined by four moderate Democrats from red states: John Breaux of Louisiana, Zell Miller of Georgia, Ben Nelson of Nebraska, and Bill Nelson of Florida.

One week later, on March 13, the Senate held another cloture vote on the Estrada nomination. And five days after that, on March 18, another. A fourth cloture vote took place on April 2, a fifth on May 5, and a sixth on May 8.

Although the vote counts varied slightly because of absent senators, Estrada’s support remained capped at 55 votes.

Some senators and outside advisers urged Frist to abolish the 60-vote threshold for cloture on judicial nominations. As we shall address in more detail, every supermajority requirement in the Senate’s formal rules, indeed every procedural obstacle to immediate Senate action (such as referrals of legislation and nominations to committees), exists at the sufferance of the Senate majority. So in theory Frist could have tried to muster a Senate majority to abolish the 60-vote threshold (just as Democratic majority leader Harry Reid succeeded in doing in 2013). But the groundwork hadn’t been laid for such a dramatic action, and many Republican senators were strongly opposed to moving so precipitously, so Frist soundly concluded that he had no choice but to continue to work for 60 votes.

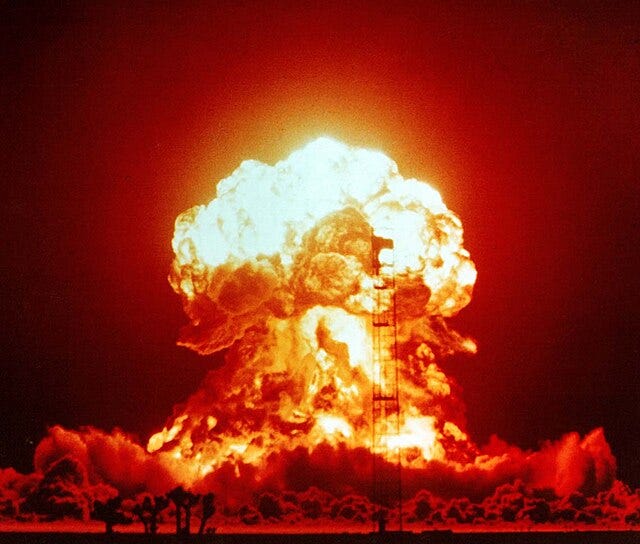

No one could be sure in advance how the politics of the Democrats’ unprecedented partisan filibuster would play out. But the fact is that a fight over a lower-court judicial nomination doesn’t get much public attention, especially when the media isn’t supportive of the nominee. Plus, far more significant news was dominating the airwaves in March 2003: the launch of the American war against Saddam Hussein’s Iraq.

Filibustering Democrats quickly determined that they weren’t paying a price with their constituents for their obstruction and that they were winning credit with liberal interest groups. So with every cloture vote, their opposition to cloture became more entrenched.

The seventh and last cloture vote on Estrada’s nomination took place on July 30. It too received only 55 votes.

In early September, Miguel Estrada decided that he had had enough. As the Washington Post reported:

Administration officials and friends said Estrada had grown increasingly frustrated over the impasse and was tired of waiting for a vote that might never come. The White House tried to forestall his withdrawal, but “he’s been unhappy for a long time, everyone’s known that,” a Republican official said.

In his letter to Bush, Estrada said “the time has come to return my full attention to the practice of law and to regain the ability to make long-term plans for my family.”

* * *

In May 2003, just three days after the fifth unsuccessful cloture vote on Estrada’s nomination, the Senate confirmed by voice vote President Bush’s nomination of John Roberts to another seat on the D.C. Circuit. As we have seen, for all that Senate Democrats pretended to need access to Estrada’s memos as an attorney in the Office of the Solicitor General, they did not even bother to request Roberts’s OSG records. Never mind that Roberts was the principal deputy in OSG—someone with significant discretionary authority—not a line attorney like Estrada. Never mind that Roberts’s own public record gave as little insight into his legal views. (Senate Democrats would demand Roberts’s OSG records two years later when they were fighting against his Supreme Court nomination.)

It quickly became clear that Senate Democrats did not regard Estrada’s nomination as unique in warranting obstruction by filibuster. On May 1, they defeated a cloture motion on Bush’s nomination of Texas supreme court justice Priscilla Owen to a seat on the Fifth Circuit. Only two Democrats voted for cloture. Over the course of 2003, they defeated three more cloture motions on Owen. They also defeated cloture motions on four other appellate nominees.

* * *

By deploying the filibuster against the Estrada nomination, Senate Democrats dramatically escalated the confirmation wars. Conservatives were especially outraged at Democrats’ unjust treatment of Estrada, as it was clear that their overarching objective was to prevent him from becoming the first Hispanic justice on the Supreme Court.

There is one more very delicate part of the story that I approach with some trepidation. As a preface, I will repeat what I wrote in my first post on Estrada’s nomination. As a longtime friend of Estrada’s, I was very much hoping to draw on his own recollections for Confirmation Tales. But for reasons that I understand and respect, he prefers not to revisit the matter of his nomination. I have therefore had no recent exchanges with him about his nomination, nor have I run any drafts or passages by him. Insofar as my post states or implies any facts or opinions, I have not drawn them from him.

The anger of many conservatives over the Democrats’ filibuster of Estrada’s nomination was intensified by the tragic personal toll that Estrada suffered. As the New Yorker reported:

During the confirmation struggle, Estrada’s wife miscarried; in November, 2004, she died, of an overdose of alcohol and sleeping pills. The death was ruled accidental by the medical examiner. [White House adviser Karl] Rove said that Mrs. Estrada had been traumatized by the nastiness of the process.

The Law of Unintended Consequences. No one foresaw Roberts’ elevation

Miguel Estrada’s best position would be Vice President, in which position he could make Charles Schumer’s daily life difficult.