On Rehnquist's Death, Bush Faces a Decision

The birth of the 'Roberts Court'

Like all history, the history of the Supreme Court sometimes pivots on small things and chance events. If Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist had lived just one month longer, there would probably never have been a “Roberts Court.”

As the long Labor Day weekend in 2005 got underway, John Roberts and Senate Judiciary Committee staffers busily prepared for the start of his confirmation hearing on Tuesday, September 6. But late Saturday evening, William Rehnquist lost his year-long battle with thyroid cancer and died at the age of 80. Suddenly there were two seats on the Court to fill, and President George W. Bush faced a choice: continue with Roberts’s nomination to replace Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, or renominate him to be chief justice, replacing the justice for whom he had once clerked.

* * *

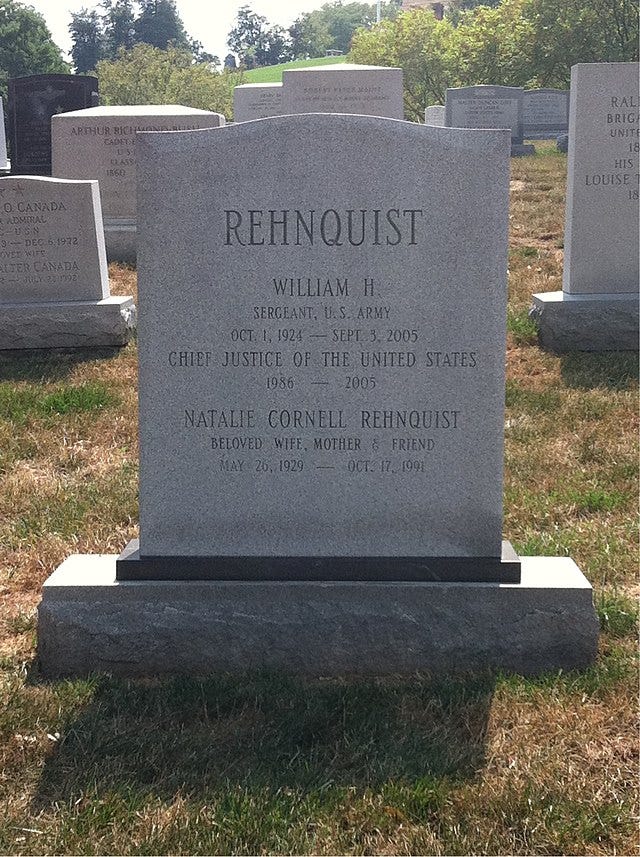

William Rehnquist had served on the Court since 1972, first as an associate justice, from 1986 on as chief justice. In his early years on the Court, Rehnquist earned the nickname the “Lone Ranger” for often being alone in his conservative legal positions. He was still well out of step ideologically with most of the other justices when Ronald Reagan nominated him to be chief. But, in the words of legal historian David Garrow, “his colleagues were unanimously pleased and supportive”:

Fourteen years of working together had built good personal relations even between Rehnquist and his ideological opposites, William J. Brennan and Thurgood Marshall. Brennan startled one acquaintance by informing him that “Bill Rehnquist is my best friend up here,” and a Washington attorney, John D. Lane, who privately interviewed all seven other Justices on behalf of the American Bar Association's Committee on the Federal Judiciary, informed the Senate Judiciary Committee that Rehnquist's nomination was met with “genuine enthusiasm on the part of not only his colleagues on the Court but others who served the Court in a staff capacity and some of the relatively lowly paid individuals at the Court. There was almost a unanimous feeling of joy.”

Rehnquist’s colleagues looked forward to his installation as “Chief” in part because they welcomed the departure of his overbearing, manipulative and less-than-brilliant predecessor, Burger, who had succeeded the legendary Earl Warren 17 years earlier. Reporters always stressed that Burger looked the part of Chief Justice of the United States, but among his fellow Justices there was virtually unanimous agreement that his skills at leading the Conference—the Justices’ own name for their group of nine—had been woefully lacking.

As Chief, Rehnquist moved much closer to the center of the Court—or the center of the Court moved much closer to him—as new conservative justices joined it. In some instances (e.g., Dickerson v. United States (2000)), it seems that he joined forces with more liberal justices so that he could assign himself the majority opinion and thus minimize the damage that a majority without him might inflict.

* * *

John Roberts was a law clerk to Rehnquist during the Court’s October 1980 term, just before entering into his five years of work in the Reagan administration. Roberts left the White House counsel’s office in May 1986, just weeks before President Reagan nominated Rehnquist to succeed Warren Burger as chief justice and Antonin Scalia to fill the associate-justice seat that Rehnquist would vacate.

Roberts returned to government service as principal deputy solicitor general in the George H.W. Bush administration. In that capacity and in his return to private practice, he argued a total of 39 cases before the Rehnquist Court and was widely regarded as the best Supreme Court advocate of his time. Rehnquist would surely have been proud of Roberts, and after stunning O’Connor into announcing her retirement decision first and seeing Roberts selected to replace her, would have hoped to spend several years together with him on the Court.

In his memorial in the Harvard Law Review, Roberts celebrates Rehnquist as a “towering figure in American law” and as someone who was “direct, straightforward, utterly without pretense—and a patriot who loved and served his country.” Rehnquist was “completely unaffected in manner,” Roberts observes, as he recounts a frequent occurrence on Rehnquist’s midday walks to relieve his back pain:

When strolling outside the Supreme Court with a law clerk to discuss a case, Chief Justice Rehnquist would often be stopped by visiting tourists, and asked to take their picture as they posed on the courthouse steps. He looked like the sort of approachable fellow who would be happy to oblige, and he always did. Many families around the country have a photograph of themselves in front of the Supreme Court, not knowing it was taken by someone who sat on the Court longer than all but six Justices.

* * *

There is no suspense, of course, to the decision that Bush made to withdraw his nomination of Roberts for O’Connor’s seat and to nominate him instead as chief justice. But it’s worthwhile to revisit the competing considerations.

From a conservative perspective, the strongest reason for Bush to proceed with Roberts’s nomination for O’Connor’s seat was that doing so would make it politically easier to pick a second nominee who was a strong conservative. The White House had already successfully sold Roberts as a suitable replacement for the much less conservative (and sometimes liberal) O’Connor. It seemed clear that the Senate would confirm Roberts, and the result would be a significant net gain in that seat. Why not pocket that gain and then nominate as chief justice someone who could effectively be pitched as the ideological equivalent of Rehnquist? Senate Democrats would still object to the nominee, of course, but the broader public would be much less inclined to do so.

Retaining Roberts for the O’Connor slot would also prevent any risk that O’Connor might decide that Rehnquist’s death meant that she should revoke her retirement decision or that the White House would be urged (as it in fact was by Judiciary Committee chairman Specter) to delay the new nomination for her slot so that she could serve for another full term.

But nominating Roberts for the position of chief justice had obvious advantages. Bush had already perceived Roberts to stand above the other candidates in being a “natural leader.” If Bush didn’t select Roberts as chief, whom would he select? And how quickly would he have to make his choice?

One possibility would be to elevate a sitting justice to the position of chief justice and to nominate someone else to that justice’s seat, but that would mean two more confirmation hearings. Plus, as Jan Crawford reports in her excellent book Supreme Conflict (2007), the two obvious contenders to be elevated—Justice Scalia and Justice Thomas—were ambivalent or opposed, and the one justice who strongly “wanted the title” of chief justice, Anthony Kennedy, was “the justice conservatives had come to despise, a view many on Bush’s legal staff happened to share.”

In the ordinary course, the Senate would not have time to confirm a new nominee as chief justice before the Court’s new term began in just one month. It might seem messy to have the chief’s position empty and only eight justices on the Court, with the liberal John Paul Stevens as acting chief justice. But if Bush nominated Roberts as chief, Roberts would likely take office before the First Monday in October, and O’Connor, having made her retirement effective upon her successor’s confirmation, would keep the Court at its full complement of nine justices.

* * *

George W. Bush did not take long to decide. Bush was facing intense criticism for his administration’s response to Hurricane Katrina, and he wasn’t going to take any risks. Plus, he believed that the position of chief should be filled first. At 8 a.m. on Labor Day, September 5, he announced that he would nominate Roberts to replace Rehnquist.

The next day, the Tuesday on which he had expected his confirmation hearing to begin, John Roberts instead served as a pallbearer, delivering Rehnquist’s casket to lie in state in the Great Hall of the Supreme Court. His hearing would begin the following Monday.

* * *

If Rehnquist had lived an additional month, Roberts would already have been appointed as an associate justice when the vacancy in the position of chief justice opened up. The White House didn’t like the idea of elevating an associate justice to the position of chief, and thus having two more confirmation battles. Plus, it would have been awkward to have a brand-new justice leapfrog Scalia. So it’s difficult to see how Roberts would have ended up as chief justice. We might instead be deep into the second decade of the Alito Court.

I could live with an Alito Court.

Why do you say Rehnquist lost his battle with cancer? His life ended with a loss?

The cancer died too, so you should call it a draw.