Rehnquist Stuns O'Connor Into Retiring

"I want to stay another year"

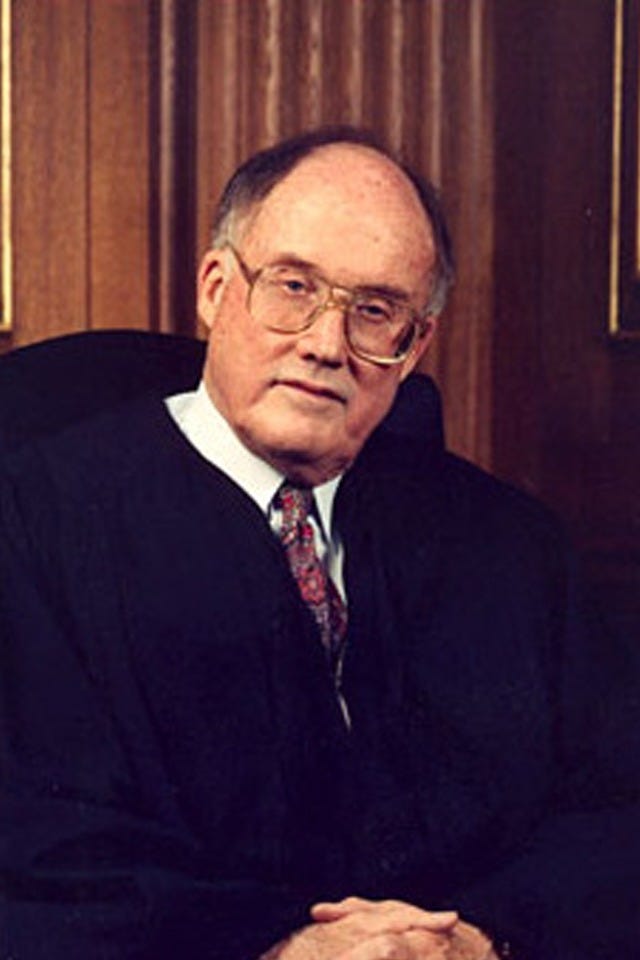

“I didn’t know we had that many people on our court.” So joked Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist on June 28, 2005—the final day of the Supreme Court’s term—as he announced the slew of seven splintered opinions in Van Orden v. Perry on the question whether the Establishment Clause allowed a Ten Commandments monument to be displayed on the grounds of the Texas State Capitol.

The 80-year-old Rehnquist had been hospitalized with thyroid cancer early that term, and he had missed four months of oral arguments as he underwent radiation and chemotherapy treatment. Everyone in attendance was awaiting an additional announcement by Rehnquist—of his retirement from the Court—but that announcement did not come.

It turns out that Rehnquist wanted to avoid a future situation in which there would be too few “people on our court”—and that his surprising solution to that problem was to persuade Justice Sandra Day O’Connor to retire.

***

Justice O’Connor announced her intention to retire on July 1, 2005. Eighteen months later, she explained to ABC News how her longtime friend Bill Rehnquist had effectively forced her decision.

O’Connor was planning to stay on the Court for another year. She “knew that Rehnquist believed emphatically that the court shouldn’t have two retirements at the same time.” As he had put it to her earlier in the year, “We don’t need two vacancies.” So she figured that he would retire in the summer of 2005 and that she could retire the following summer.

But in early June 2005, Rehnquist “stunned [O’Connor] by telling her: ‘I want to stay another year.’” That meant that O’Connor had to “retire now or be prepared to serve two more years.” O’Connor’s beloved husband was suffering from Alzheimer’s, and she couldn’t see putting off caring full-time for him for another two years. So she realized it was her time to retire.

Rehnquist and O’Connor dated each other 55 years earlier as law students at Stanford, and a year later Rehnquist wrote to O’Connor to ask her to marry him: “To be specific, Sandy, will you marry me this summer?” That proposal received a negative response, but Rehnquist’s proposal in 2005 fared much better.

***

Rehnquist was a consummate poker player, and a cynic might wonder if he was deliberately putting the squeeze on O’Connor. It strikes me as much more likely that he thought it a generous act of friendship to enable her to spend more time with her husband. As a widower for over a decade, Rehnquist had his judicial work very much at the core of what sustained him.

Why Rehnquist was so concerned about the possibility of two Supreme Court vacancies at the same time is not clear. The last time that two vacancies arose at the same time was in mid-September of 1971, when Justice Hugo Black and Justice John M. Harlan II, both in poor health, announced their retirements within six days of each other. Richard M. Nixon promptly nominated Lewis F. Powell Jr. to replace Black and Rehnquist himself to replace Harlan, and both were confirmed by a Democrat-controlled Senate in December 1971.

The Court that Rehnquist joined back then might well have felt understaffed for the more than seventy (!) oral arguments that it heard before Powell and Rehnquist came on board, and some of the cases that were argued—most prominently, Roe v. Wade—had to be re-argued later. But that experience would seem much more an argument against a justice’s retiring as late as September (or even in the middle of the Court’s term).

What’s more, insofar as Rehnquist was concerned that two vacancies might leave the Court shorthanded, one way to address that concern would be for the justices to retire effective upon the confirmation of their successors—and to continue to work in the meantime. That is in fact the course that O’Connor selected, and she ended up working on the Court until the end of January 2006 and took part in twenty-five of the Court’s decisions.

Perhaps Rehnquist feared that the existence of two vacancies would somehow delay the president from filling either. But Rehnquist’s own experience in 1971 would not seem to justify that fear. And although the confirmation wars had intensified over the intervening decades, the ample majority that Republicans enjoyed in the Senate in 2005 promised speedy confirmation.

***

In her tribute to Rehnquist in the Harvard Law Review, O’Connor writes:

The Chief was a betting man. He enjoyed making wagers about most things: the outcome of football or baseball games, elections, even the amount of snow that would fall in the courtyard at the Court. If you valued your money, you would be careful about betting with the Chief. He usually won. I think the Chief bet he could live out another Term despite his illness. He lost that bet, as did all of us….

Rehnquist died on September 3, 2005, just before the confirmation hearings for O’Connor’s designated successor were scheduled to begin. Ironically, by persuading O’Connor to retire, Rehnquist ended up creating the two-vacancy scenario that he had sought to avoid and pushing confirmation of one of the vacancies at least two months into the Court’s new term.