George W. Bush Aims for Strong Start on Judicial Nominations

But lots of challenges lie in his way

I’ve devoted my past twenty or so posts to the battles over George W. Bush’s nominations of John Roberts, Harriet Miers, and Samuel Alito to the Supreme Court from July 2005 through January 2006. As we have seen, those battles were very much shaped by earlier fights over Bush’s lower-court nominees. Let’s now circle back to the beginning of Bush’s presidency to take a careful look at some of those fights.

* * *

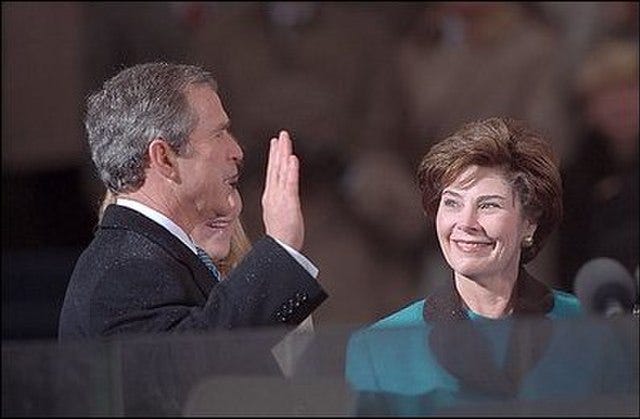

When Bush was inaugurated on January 20, 2001, he faced several daunting challenges on judicial nominations.

1. For starters, the White House needed to be ready in the event of a Supreme Court vacancy. Chief Justice Rehnquist was 76 years old and had long been suffering from serious back pain. Justice John Paul Stevens would soon turn 80. Justice Sandra Day O’Connor was only 70, but her husband was reported to have told friends that she wanted to step down.

Bush knew better than to repeat Bill Clinton’s blundering. As we have seen, just two months into Clinton’s presidency in 1993, Justice Byron White informed him of his decision to retire. Clinton’s tortuous path to nominating Ruth Bader Ginsburg took an extraordinary 86 days, and his vacillations invited widespread ridicule.

White House counsel Alberto Gonzales and his deputy counsel Tim Flanigan promptly assembled an outstanding team of conservative lawyers with a deep commitment to building a strong judiciary. Among them were a future Supreme Court justice (Brett Kavanaugh), a future Solicitor General (Noel Francisco), and a future Associate Attorney General (Rachel Brand). In the early months of 2001, the White House team drew up a list of a dozen or so Supreme Court candidates, conducted extensive reviews of their records, and compiled lengthy memos.

2. Bush also wanted to make a strong start on lower-court nominations. He inherited from Clinton roughly 80 vacancies, including two dozen on the federal courts of appeals. White House lawyers divvied up the seats and completed comprehensive forms on each candidate.

Gonzales formed a judicial-selection committee that held weekly meetings to push the process forward. In addition to White House lawyers, participants in the meetings included top lawyers from the Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Policy and sometimes even Attorney General John Ashcroft. Senior White House adviser Karl Rove, drawing on his encyclopedic on-the-ground political knowledge, was especially valuable in helping the committee navigate how various nominations would play with home-state senators.

Gonzales, Flanigan, and the line lawyers responsible for particular seats would then prepare a summary of their recommendations for President Bush and meet with him to discuss the candidates.

3. Hitting the ground running on judicial nominations was made all the more difficult by the fact that the presidential election wasn’t resolved until the Supreme Court’s decision in Bush v. Gore on December 12, 2000. So Bush had only half the usual time—around five weeks—to focus on beginning to operate the White House.

4. The composition of the Senate presented another huge challenge. Everyone recalls how incredibly close the presidential election was, with Bush’s clinching victory in Florida coming by a margin of only 537 votes out of the nearly six million ballots cast in the state. It’s easy to forget that the Senate races generated a Senate evenly divided between two parties for the first time since 1881.

Thanks to Vice President Dick Cheney’s tie-breaking vote, Republicans became the majority part on January 20, 2001. But the 50-50 divide among the senators led to an extraordinary power-sharing agreement under which (among its various provisions) all Senate committees would have an equal number of Republican and Democrats. Under the Judiciary Committee’s usual practice, a tie vote on a nomination meant that the nomination would not be reported to the Senate floor for a confirmation vote. But the agreement provided that in the event of a tie vote in committee, the majority leader could move to discharge the matter from committee.

In short, the White House had no margin for error with Republican senators in the Judiciary Committee. If a Republican senator even missed a committee vote, a nomination might be imperiled. And even when all Republican senators on the committee supported a nomination, the opposition of all Democratic senators would force the nomination to go through additional hoops in order to receive a final floor vote.

5. Perhaps the biggest obstacle the White House faced was the determination of Senate Democrats to escalate the judicial-confirmation wars. As the New York Times reported, in April 2001 Senate Democrats attended a retreat “where a principal topic was forging a unified party strategy to combat the White House on judicial nominees”:

The senators listened to a panel composed of Prof. Laurence H. Tribe of Harvard Law School, Prof. Cass M. Sunstein of the University of Chicago Law School and Marcia R. Greenberger, the co-director of the National Women's Law Center, on the need to scrutinize judicial nominees more closely than ever. The panelists argued, said some people who were present, that the nation's courts were at a historic juncture because, they said, a band of conservative lawyers around Mr. Bush was planning to pack the courts with staunch conservatives.

“They said it was important for the Senate to change the ground rules and there was no obligation to confirm someone just because they are scholarly or erudite,” a person who attended said.

* * *

Things would soon get much worse for President Bush.