2004 Senate Victories Pave Smooth Path to Supreme Court Confirmation

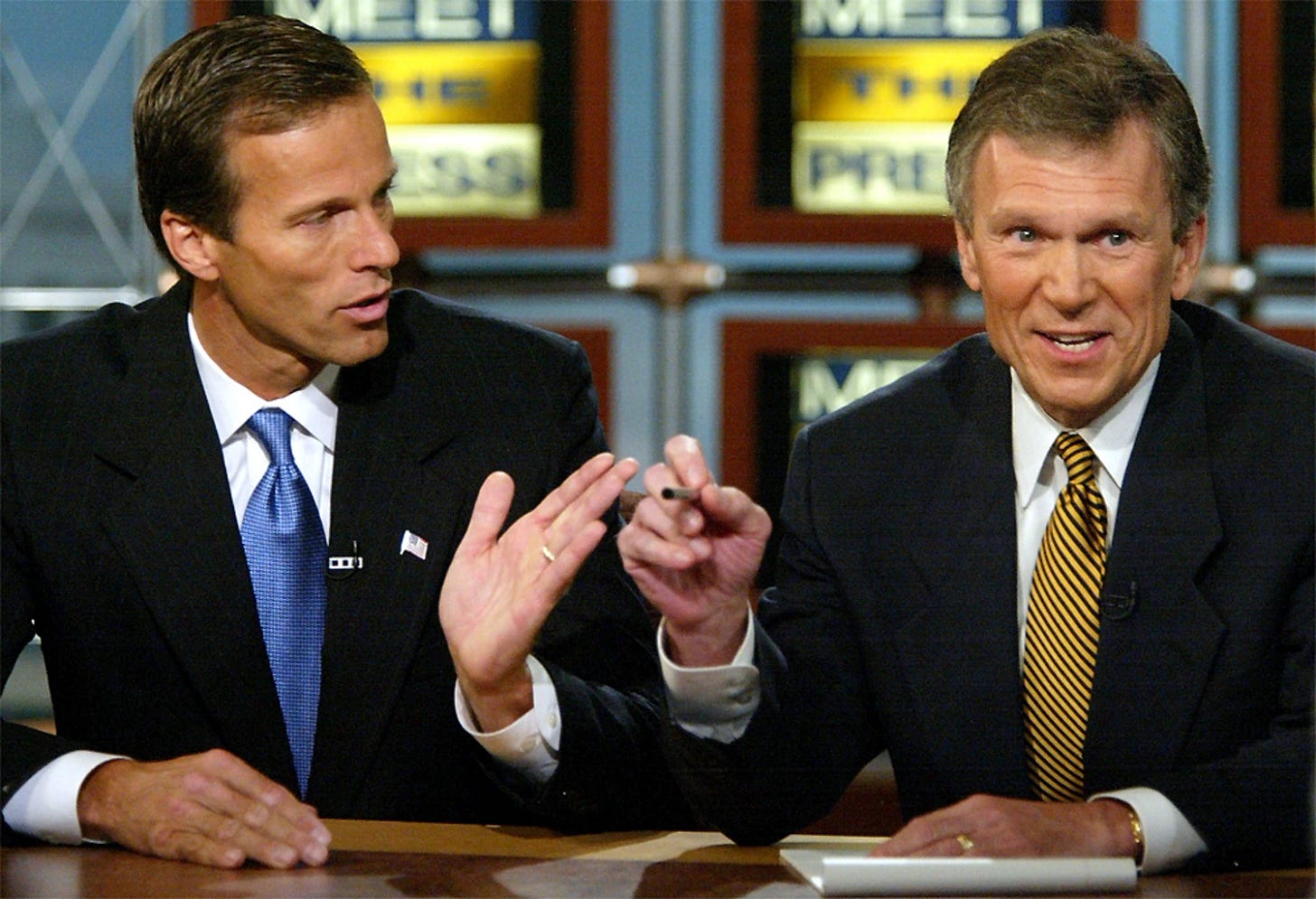

John Thune ousts Democratic leader Tom Daschle

In addition to giving him a second presidential term, Election Day in 2004 delivered George W. Bush important victories in the Senate that promised to pave a smooth path for any Supreme Court nomination that he would make. Senate Republicans gained a net four seats and expanded their majority from a very tight 51-to-49 edge to a very comfortable margin of 55 to 45. In a particularly consequential race in South Dakota, Republican challenger John Thune slammed Democratic leader Tom Daschle for his obstruction of Bush’s judicial nominees and succeeded in ousting Daschle.

These victories ensured that Senate Republicans would not need any help from Senate Democrats to muster a majority to confirm a strong conservative nominee to the Supreme Court. They also eliminated any prospect that Democrats would wage a serious filibuster effort against such a nominee.

* * *

If a president is trying to get a Supreme Court nominee confirmed, it helps a lot if senators of his political party have a majority in the Senate. That’s true for the obvious reason that if all of the members in the majority support the nominee, the nominee will have the votes to win a roll-call vote on confirmation. It’s also true because the Judiciary Committee chairman (who of course is from the party that controls the Senate) can help a nominee in lots of ways—for example, by praising the nominee to the media, by expediting the hearing, by working with the White House on any contested process issues, by running the hearing effectively, and by reporting the nomination promptly to the full Senate.

But it’s not just a question of having control of the Senate. The margin of control also matters. If the margin is very narrow—say, a 50-50 Senate in which the Vice President casts the tiebreaking vote or 51-49—one risk is that a senator on either wing of the president’s party might try to exert leverage at the outset over whom the president nominates: “Pick someone who is clearly committed to my pet cause, or you’re not going to get my vote.” A closely divided Senate also provides little margin for error. If one or two same-party senators flip, the nomination risks being defeated unless offsetting votes come from minority-party senators. The prospect of such drama isn’t attractive to a White House, which much prefers a narrative in which Senate confirmation appears to be foreordained.

Supporters of judicial conservatism are fortunate in one large way that Supreme Court vacancies arose in 2005 rather than in George W. Bush’s first term. At the outset of Bush’s presidency, the Senate was divided 50-50, with Vice President Cheney’s tiebreaking vote giving Republicans control. But Jim Jeffords announced in May 2001 that he was abandoning the Republican party and as an independent would caucus with the Democrats. So that gave the Democrats control of the Senate by a 51-to-49 margin, and Patrick Leahy displaced Orrin Hatch as chairman of the Judiciary Committee. Bush would have had a very difficult time getting a strong conservative nominee confirmed in that environment, and he also would have had very few candidates of prime age to choose from, as he had not yet had much of an opportunity to begin seeding the federal courts of appeals.

Republicans regained control of the Senate after the 2002 elections, but only by a 51-to-49 margin. If a vacancy had arisen in 2003 or 2004, Bush would have been constrained by the need to keep more than one of a half dozen or so liberal-to-moderate-liberal Republicans (e.g., Lincoln Chafee, Olympia Snowe) from defecting. He might well have succeeded, but he certainly would not have had the free rein he had in 2005.

* * *

Controversy over Senate Democrats’ obstruction of Bush’s judicial nominees played an important role in earning Republicans the 55-seat majority that they carried into 2005. Nothing illustrates that better than the Senate race in South Dakota between Tom Daschle and John Thune.

Daschle, the Democratic leader in the Senate since 1995, was seeking election to his fourth term. He had won his previous re-election races by huge margins (33 and 26 points).

Daschle championed the unprecedented campaign of partisan filibusters that Senate Democrats launched against Bush’s appellate nominees in 2003. (Much, much more to come on the filibuster campaign when I circle back to Bush’s appellate nominations.) Thune made Daschle’s obstruction of Bush’s judicial nominees a major part of his campaign, so much so that Daschle observed in a national debate on the television program Meet the Press that “John keeps coming back to this.” In that debate, Thune got very specific:

Let's talk about the people that you're not giving a vote, Tom…. You know, Janice Rogers Brown, Priscilla Owen, Charles Pickering, Bill Pryor, Miguel Estrada, Bill Myers--you go right down the list. These people didn't get a vote. Now it's one thing to say that, you know, you're confirming a certain percentage, but these people deserve a vote. The filibuster has never been used in the history of this country to deny appellate court nominees an opportunity and an up-and-down vote in the United States Senate. Under Tom Daschle, that is the first time that has happened.

Daschle resorted to lying in response, “That’s not true.”

Throughout the campaign, Bush, Cheney, and Senate Republican leader Bill Frist joined Thune in slamming Daschle for leading the filibuster of judges. Thune himself was astonished by the impact that judicial nominations had in his campaign:

It was amazing to me. Early on I’d make speeches about openings on the Supreme Court, or getting these appellate nominees confirmed, and people would look at me like, “Who cares?” Toward the end of the campaign, I’d make that speech and it was one of the biggest applause lines.

On Election Day, Thune eked out a victory over Daschle, 50.6% to 49.4%.

* * *

It is unlikely in any event that Senate Democrats would have undertaken a serious filibuster effort against any Supreme Court nominee in 2005. It was one thing to filibuster appellate nominees. Democrats counted on hardly anyone paying attention to those nominations. It would have been a very different thing to filibuster a Supreme Court nominee in the national spotlight. And the political reality was that Bush would have no incentive to nominate anyone so unappealing that Democrats would dare to try to filibuster the nominee.

But Daschle’s defeat put the final nail in the coffin of any possible filibuster strategy, as it emphatically illustrated that Senate Democrats were on the losing end of the politics of judicial confirmations.

To be sure, at the very tail end of Samuel Alito’s confirmation process, when, as NPR put it, Senate Democrats “appeared resigned” to Alito’s confirmation, Democratic senator John Kerry called for a filibuster from a ski resort in Davos, Switzerland. But the ridicule that Kerry’s call earned—the first time anyone had ever yodeled for a filibuster, the White House joked—signaled that no one was taking it seriously.

Only 24 Democrats ended up joining Kerry in voting against cloture. And those who did—including future president Barack Obama—would have ample reason a decade later to regret their clear repudiation of the notion that every Supreme Court nominee deserves an up-or-down vote on confirmation.