Why the Federalist Society Has Been a Great Success

Spilling the secrets

Today is the opening day of the Federalist Society’s annual National Lawyers Convention. Two or three thousand lawyers, judges, and law students from across the country will gather for the convention’s various activities: panel discussions, speeches, and the centerpiece Antonin Scalia Memorial Dinner.

The Federalist Society is an incredible success story. From its founding by a handful of law students in 1982, it has been far and away the organization most responsible for the remarkable ascendancy of the conservative legal movement, an ascendancy that has culminated in an achievement that was unimaginable not long ago: the establishment of a strong conservative majority on the Supreme Court.

The Federalist Society’s success has led many on the Left—and, more recently, some envious folks on the Right—to revile and demonize it. But its critics routinely display that they do not understand how it operates and how it has succeeded.

* * *

Perhaps you think it improper, even egregious, for federal and state judges to be active in an organization that files amicus briefs, including on hot-button issues like abortion, in the Supreme Court and other courts, that adopts resolutions on the broad range of public-policy topics, that rates federal judicial nominees, and that even tries to mobilize the public “to send messages directly to your elected officials.”

I certainly do. That’s one of many reasons to condemn the American Bar Association, the liberal geriatric guild that falsely proclaims itself the “national voice of the legal profession.”

In sharp contrast to the ABA, the Federalist Society does “not lobby for legislation, take policy positions, or sponsor or endorse nominees and candidates for public service.” It does not submit amicus briefs. It does not undertake to enlist the public in political undertakings. And it has never done any of these things.

And therein lies one of the great keys to its success.

* * *

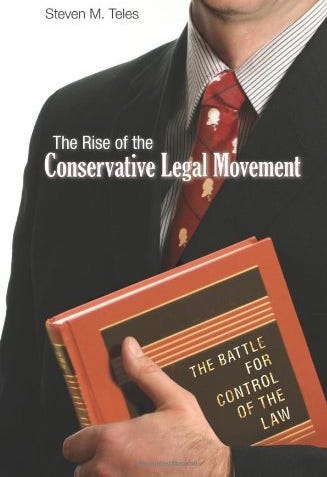

In 2008, political scientist Steven M. Teles published an outstanding book, The Rise of the Conservative Legal Movement, in which he undertakes to “explain how the conservative legal movement, outsmarted and undermanned in the 1970s, became the sophisticated and deeply organized network of today.” He devotes one large chapter of his book to the Federalist Society. That chapter remains as insightful and informative as it was in 2008.

As Teles sums it up, the Federalist Society “was founded to dislodge what it saw as the ‘hegemony’ of liberalism in the key institutions of the legal profession,” and it “represents, without a doubt, the most vigorous, durable, and well-ordered organization to emerge from this rethinking of modern conservatism’s political strategy.”

Teles observes that “[t]here is a strong tendency in most of the popular writing on the [Federalist] Society to conflate the activities of the organization itself with those of its members”—with the activities, that is, of individuals who on their own, and apart from any direction or supervision by Federalist Society leaders, work to advance conservative or libertarian legal causes. But this conflation obscures why it has been so successful.

The Federalist Society has been diligent in maintaining what Teles calls “boundary maintenance”: Its early leadership made the “key decision … to narrow its mission to facilitating the activism of its members and influencing the character of intellectual debate rather than directly influencing the actions of government itself.” The Federalist Society itself is “focus[ed] almost exclusively on fostering debate and providing services to its members.” As Teles explains, the Federalist Society’s “emphasis on debate, rather than just sponsoring conservative speakers,” grew out of the conviction that in a fair debate the best ideas will prevail. Its commitment to debate “made the organization open and attractive to outsiders, moderated factional conflict and insularity, and had a tendency to prevent the members’ ideas from becoming stale from a lack of challenge.”

By defining its own mission and activities narrowly, the Federalist Society has indirectly played an invaluable “networking function” for the broader conservative legal movement. It has recruited law students and lawyers into the movement by exposing them to conservative legal ideas and giving them leadership opportunities. It has connected them with each other and with judges, law professors, and state solicitors general. And it has created a transmission belt that over the decades has moved law students from law school to prestigious judicial clerkships to a variety of important positions in the executive branch in the federal and state governments to judgeships, including on the Supreme Court.

I’m pleased to have played my own small role in the Federalist Society: I would estimate that I have spoken at more than 200 Federalist Society events across the nation over the past two decades.

* * *

Almost invariably, when critics attack the Federalist Society, they are actually complaining not about anything that the organization itself has done but about things done or said by individuals in the broader network that it has helped to build.

This year’s Federalist Society convention features some thirty or so panels and debates, with more than 100 speakers, many of whom are liberal law professors, government officials, or activists. The lawyers and students who attend will hear excellent presentations, connect with each other, and converse with the many judges holding court. This is the Federalist Society in action.

A high and much appreciated tribute from a scholar who himself has contributed so much to legal debate.