The Mystery of Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.'s Recess Appointment

What did Theodore Roosevelt actually do?

On its page for Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., the Federal Judicial Center tells us:

President issued recess appointment to Supreme Court of the United States, August 11, 1902, and subsequently cancelled appointment.

Puzzled by this entry, I did some research—and became more puzzled. On further research, some things cleared up, but it’s still a mystery whether Theodore Roosevelt ever actually issued a recess appointment to Holmes.

The little-known episode also illustrates how a president and a senator can have very different conceptions of what proper consultation over a Supreme Court pick consists of.

***

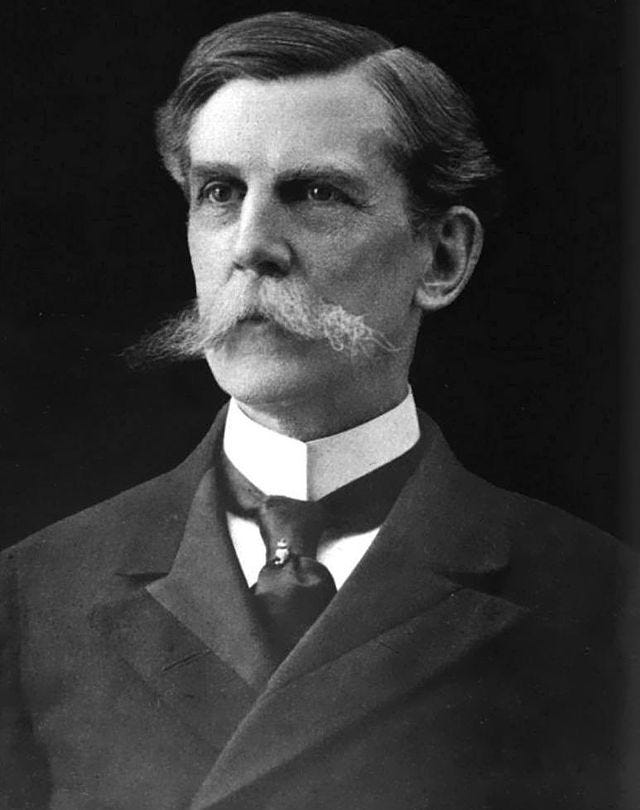

Horace Gray, whom conscientious Confirmation Tales readers will recall as the tallest justice (six feet six inches) in the history of the Supreme Court, had been a wunderkind. He graduated from Harvard College at the age of 17 and from Harvard law school at the age of 21. At the age of 36, he became the youngest justice ever appointed to the Massachusetts supreme court. He served for nearly two decades on that court, including as chief justice, until Chester Arthur appointed him to the Supreme Court in 1882.

Twenty years later, in 1902, Justice Gray was an elderly man (74 was much older then than it now seems) and in poor health, and he was contemplating retiring from the Court.

On July 1, 1902, the Senate adjourned for an intersession recess. Its next session would begin on December 1, 1902.

In a letter dated July 7, 1902, Senator Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts informed Roosevelt that Gray’s “family all wish him to resign and are urging him to do so at once.” Lodge told Roosevelt to expect Gray’s resignation “very soon.” Lodge strongly recommended Holmes. But he warned Roosevelt that George Hoar, the senior senator from Massachusetts (and, like Roosevelt and Lodge, a Republican), “does not like” Holmes: “I do not know exactly why. All he has said to me is of a vague character.”

Two days later, in a letter dated July 9, Justice Gray informed Roosevelt that, having been “advised by my physicians that to hold the office of Justice of the Supreme Court for another term may seriously endanger my health,” he intended to resign. He would have his resignation “take effect immediately, but for a doubt whether a resignation to take effect at a future day, or on the appointment of my successor, may be more agreeable to you.”

Roosevelt promptly responded to Gray, in a letter dated July 11:

It is with deep regret that I … accept your resignation…. If agreeable to you, I will ask that the resignation take effect on the appointment [sic] of your successor.

Gray, in a letter back to Roosevelt, confirmed that “my resignation is to take effect on the appointment of my successor.”

On July 25—according to G. Edward White’s biography of Holmes—Roosevelt had a “secret meeting” with Holmes at Roosevelt’s summer home on Long Island. Roosevelt offered the Supreme Court seat to Holmes, and “Holmes accepted the offer.”

That same day, Roosevelt then wrote to Senator Hoar that “Judge Gray has resigned” and that he has “decided to offer the place” to Holmes, “but I do not wish to announce anything until I hear from you.”

In a letter dated July 28, Hoar responded with exasperation over the poor quality of Roosevelt’s consultation with him:

If the matter be decided, I do not understand what it is that you expect or desire to hear from me. As a Massachusetts lawyer, as the senior senator from the New England Circuit, and as Chairman of the Law Committee of the Senate, I naturally feel great interest in the appointment of a Judge of the Supreme Court of the United States from my own Circuit and my own state.

Hoar expressed his dissatisfaction with Roosevelt’s keeping Gray’s resignation a secret and, although Roosevelt’s letter was not explicit on the point, with what he understood to be Roosevelt’s intention to recess-appoint Holmes to the Court:

The old method, pursued, so far as I know, by all your predecessors, in making these great and irrevocable appointments, has been to let the public know of the vacancy, to allow a reasonable time for all persons interested, especially the members of the legal profession, and the representatives of the States immediately concerned, to make known their opinions and desires, and with, I think, two exceptions, to announce and make the nominations when the Senate was in session. One of these exceptions was the case of Ch. Justice Rutledge, who was rejected by the Senate after actually entering upon his duties. The other was the case of Judge Curtis, of whose eminent fitness no man could doubt.

This method of proceeding has worked admirably heretofore. You are, however, the sole and propre [sic] judge whether another way be better.

(As we have seen, in addition to John Rutledge and Benjamin Curtis, there had been seven other justices who had been recess-appointed.)

***

Despite Senator Hoar’s objections, Roosevelt evidently proceeded with his plan to recess-appoint Holmes. In an article dated August 11, 1902 (but published on August 12), the New York Times reported:

The President to-day appointed Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Massachusetts, to be an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court, because of the vacancy caused by the retirement of Justice Horace Gray on account of ill-health.

(The article made no mention of the fact that Gray’s decision to retire had not been previously known.)

Department of Justice records reflect that a commission to recess-appoint Holmes to the Supreme Court was dated August 11. (I’m drawing here on the account by Henry B. Hogue of the Congressional Research Service.)

Also on August 11, Roosevelt wrote this one-sentence letter to Justice Gray:

To-day I have announced the appointment of Judge Holmes, and with renewed regret I accept your resignation.

Have in mind that Roosevelt requested, and Gray agreed, that Gray’s resignation would “take effect on the appointment of your successor,” not merely on Roosevelt’s announcement of the person whose nomination he intended to submit to the Senate. If Roosevelt’s word choice is taken seriously, Roosevelt understood that he had recess-appointed Holmes. Indeed, Roosevelt’s phrasing of Gray’s resignation seems to have been designed with a recess appointment in mind. (One problem with that phrasing is that there was no vacancy to which Roosevelt could recess-appoint Holmes until after Gray had resigned.)

***

At their secret meeting on July 25, Roosevelt and Holmes evidently neglected to discuss Roosevelt’s intention to recess-appoint Holmes. It turns out that Holmes did not want to be recess-appointed.

In the same column of the August 12 New York Times is an article dated August 11 that bears the title “Justice Holmes Will Accept.” The article reads:

“If the report that I have been named for a seat on the Supreme Bench of the United States is true I shall certainly accept,” said Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes at his Summer home to a reporter to-night. “Personally I know nothing of the matter beyond what you tell me, my first intimation that I had been, or was going to be, chosen coming from the press.” [False!]

“When will you resign your present position?” was asked.

“Hardly before the Senate approves the President’s nomination. It must be confirmed by the Senate, you know,” replied the Justice.

On August 17, Holmes wrote a letter to Roosevelt. I haven’t been able to locate that letter, but it seems clear from Roosevelt’s response to it that Holmes informed Roosevelt that he did not want to be recess-appointed and that he feared that a recess appointment might jeopardize the prospect that the Senate would subsequently confirm his nomination to a lifetime position. A recess appointment would expire when the Senate adjourned its next session—which date Holmes would have anticipated would be March 3, 1903. Why invite any risk to his nomination?

Here is Roosevelt’s August 19 response:

The Senate is not too large for a lunatic asylum, and if there is any opposition whatever to your confirmation, I shall certainly feel that it fulfills all the conditions of one. Seriously, I do not for one moment believe that a single vote will be cast against your confirmation. I have never known a nomination to be better received, but I shall write to Lodge and get his advice on the point you raise. Then if necessary I shall withdraw my official tender of the place to you and wait until the Senate convenes.

Two days later, Roosevelt wrote to Holmes:

After consulting one or two people, I feel that there is no necessity why you should be nominated [sic] in the recess. Accordingly I withdraw the recess appointment which I sent you, and I shall not send you another appointment until you have been confirmed by the Senate….”

***

In his very careful account of this matter (pp. 662-665 of this article), Henry B. Hogue states that he “could find no evidence that [Roosevelt] signed the commission [dated August 11, 1902], nor that Holmes received a commission for a recess appointment.” Indeed, Hogue discovered that Holmes informed Senator Lodge that while Roosevelt wrote that he was “withdrawing the recess appointment which he sent me[,] I received nothing unless he refers to one conversation, which I understood to be merely a communication of his intent.” (Emphasis in original.) Hogue therefore concludes that Roosevelt “did not complete the process of making a recess appointment.”

Hogue may well be right that, contrary to Roosevelt’s own apparent understanding, Roosevelt never issued a recess-appointment commission to Holmes. I would not exclude the possibility, though, that Holmes might have found it politic to minimize the risk that it would ever be discovered that Roosevelt had issued him a recess appointment—and therefore chose to deceive even Lodge on the point, just as he had deceived the public by telling the New York Times on August 11 that he “kn[e]w nothing of the matter beyond what you tell me, my first intimation that I had been, or was going to be, chosen coming from the press.”

Hogue reports that the “word ‘canceled’ is written several times over” the Department of Justice record of the August 11 commission by which Roosevelt would have recess-appointed Holmes. But if Roosevelt did ever send Holmes a commission for a recess appointment (as Roosevelt’s own account indicates he did), it’s doubtful that he could “withdraw” or “cancel” it. As Chief Justice Marshall wrote in Marbury v. Madison (1803):

Some point of time must be taken when the power of the Executive over an officer, not removable at his will, must cease. That point of time must be when the constitutional power of appointment has been exercised. And this power has been exercised when the last act required from the person possessing the power has been performed. This last act is the signature of the commission.

In any event, no appointment, recess or otherwise, can be effective in placing an individual in an office without that individual’s acceptance of the appointment. So Holmes’s objection meant that no recess appointment was ever completed.

***

Horace Gray died on September 15, 1902. Roosevelt submitted his nomination of Holmes to the Senate on the second day of its session, December 2, 1902. The Senate confirmed Holmes’s nomination by voice vote on December 4. Holmes took his seat on December 8 and continued in service until 1932.

Senator Hoar ended up acquiescing in Holmes’s selection. As one colorful account that might well offer continuing insight into Senate prerogatives explains, Senator Lodge

came to realize that … what [Hoar] most seriously resented was the fact that rightful deference had not been made to the Senior Senator from Massachusetts himself. “I feel about it,” [Hoar] had written candidly to Lodge on August seventh, “somewhat as the [fellow] did when he heard that a neighbor was going to shoot his dog. He said with great indignation, ‘If he gives me notice and then shoots my dog, I don't care, but if he shoots my dog without giving me notice, I shall be mad.’”