*That* Sure Wasn’t In My Talking Points

Why I nearly fell off my chair

Early on a cold Saturday morning in March 1993, I headed to the NBC News studio to accompany Senator Orrin Hatch for an interview on NBC’s Today show. The day before, Justice Byron White had informed President Clinton that he would retire when the Court’s term ended (in late June or early July).

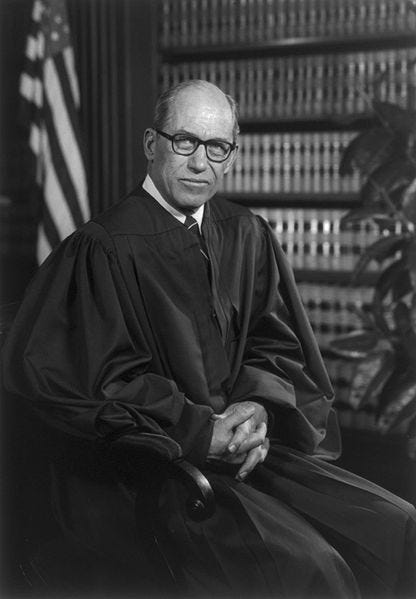

Byron White was an extraordinary man. Raised in rural Colorado, he was an All-American halfback at the University of Colorado as well as class valedictorian. A Rhodes Scholar, he went on to attend Yale Law School, and to graduate first in his class, while also playing in the NFL, where he led the league in rushing and was the NFL’s highest-paid player. (I’m drawing from his Wikipedia entry.)

In his mid-70s, White was still a rock of a man when I met him during my clerkship with Justice Scalia. I can attest that his reputation for a crushing handshake was well deserved. White had by that time stopped playing basketball with the clerks on the “highest court in the land”—the basketball floor above the courtroom—so I happily missed out on the experience of being knocked to the floor by the bruising elbows he threw in getting rebounds.

John F. Kennedy appointed White as Deputy Attorney General in the Department of Justice in 1961. But when Justice Charles Evans Whittaker resigned after a nervous breakdown in the spring of 1962, JFK appointed White to fill his vacancy. White was 44 years old. The Senate confirmed White’s nomination by voice vote, a mere eight days after JFK submitted it. By 1993, White was the longest-serving justice then on the Court.

White’s judicial approach was difficult to categorize. A liberal on civil rights and federal powers, he was one of the two dissenters in Roe v. Wade in 1973 and, just the previous June, had voted to overturn Roe. He wrote the majority opinion in Bowers v. Hardwick (1986) that held that the Constitution does not protect a right to homosexual sodomy, and, as Linda Greenhouse put it, he was a “reliable conservative” on the “rights of criminal defendants.”

White was also the only sitting justice who had been appointed by a Democratic president. Justice Thurgood Marshall, appointed by LBJ in 1967, had resigned in 1991. It had been more than two dozen years since a Democratic president had nominated a Supreme Court justice. Over those years, Republican presidents had appointed ten justices to the Court—Nixon appointed four, Ford one, Reagan three, and George H.W. Bush two—but most of those justices had (for reasons I hope to address down the road) disappointed conservatives.

The Supreme Court confirmation wars had also escalated dramatically in recent years, first with the defeat of Robert Bork’s nomination in 1987 and then with the bitter battle over Clarence Thomas’s nomination in 1991. In June 1992, the chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, a fellow by the name of Joe Biden, had given a long Senate floor speech in which he warned President George H.W. Bush not even to make a nomination if a Supreme Court vacancy arose during the summer of that election year.

Conservative activists in D.C. were itching for payback. Clint Bolick, then with the libertarian Institute for Justice (and now a justice on the Arizona supreme court), warned: “If Clinton makes this nomination an ideological battleground, it will turn into a judicial Armageddon.”

There were 57 Democrats in the Senate, but eight or ten of them could plausibly be viewed as moderates. As the leading Republican on the Senate Judiciary Committee, Senator Hatch would be expected to try to condition the environment to make it as costly as possible for Clinton to select a liberal justice. NBC News was eager to learn Hatch’s views, and I had provided him with a one-pager of solid talking points on standing strong against liberal judicial activism.

The interview had barely started when Hatch volunteered that he thought that Marian Wright Edelman would make a fine Supreme Court justice.

What?!? Seated in front of the studio stage, I nearly fell off my chair. That sure wasn’t in my talking points. Marian Wright Edelman was prominent back then as a longtime mentor to Hillary Clinton and as founder and leader of the Children’s Defense Fund, an activist group that, then as now, used the rhetoric of children’s rights to push an array of liberal policies. She was anathema to many conservatives, and although she had a Yale law degree and had once practiced law, the activist career path that she had chosen made it easy to depict her as poorly qualified to be a Supreme Court justice. So, I wondered in shock, why the heck was Hatch praising her as a possible candidate?

Hatch’s interview didn’t get much better in my eyes after that. When it ended, I bit my tongue until Hatch and I left the studio and got into the parking lot.

“Why the heck did you say that Marian Wright Edelman would make a fine Supreme Court justice?,” I bristled.

“Don’t worry, he’ll never nominate her,” Hatch responded.

But, I objected, his praise for her was telling the White House that Republicans would not fight any Clinton nominee on the ground of judicial philosophy—that even a very liberal nominee would not face serious opposition.

It turns out that Hatch was eager to send that very message. By doing so, he actually ended up having considerable influence over whom Clinton selected both for Byron White’s vacancy and especially for the seat that opened up in 1994 when Justice Harry Blackmun retired.

I’ll explore the why and the how of this matter in future posts. But for now I’ll highlight a second reason that Hatch would have been eager to praise Marian Wright Edelman. Hatch’s political advisers were concerned that the confirmation hearings in 1991 for Clarence Thomas had hurt Hatch’s standing with women in Utah, who were said to think that he had been too harsh in his questioning of Anita Hill. Never mind that he had not in fact asked any questions of Anita Hill. So Hatch’s praise for an African-American woman as a Supreme Court candidate would address this perceived political vulnerability.