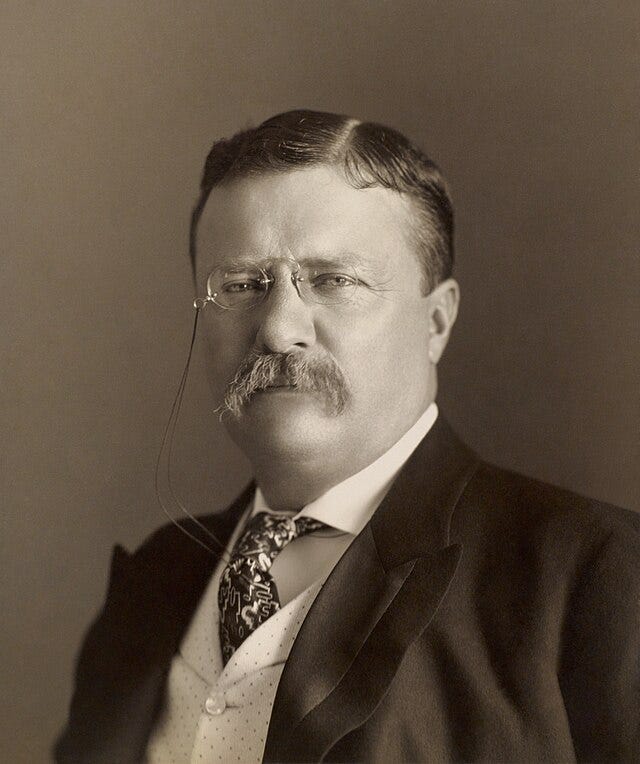

Teddy Roosevelt Quickly Regrets Appointing Justice Holmes

“I could carve out of a banana a judge with more backbone"

Theodore Roosevelt had a strong understanding of what he wanted in a justice when he considered naming Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. to the Supreme Court in 1902. He carefully vetted Holmes—including in a secret interview—and declared himself “entirely satisfied” with him. But barely a year after putting Holmes on the Court, he was outraged by a Holmes dissent: “I could carve out of a banana a judge with more backbone than that,” he declared. Two years later, in a letter to his friend Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, who had urged him to select Holmes, Roosevelt broadly labeled Holmes “a bitter disappointment.”

In Roosevelt’s distinctively vivid and outsized way, he provides an enduring lesson in how presidents are disposed to misjudge Supreme Court candidates.

* * *

Senator Lodge informed Roosevelt in July 1902 that Justice Horace Gray would soon retire, and he urged Roosevelt to pick Holmes to replace him. In a remarkable letter, Roosevelt immediately wrote back to Lodge and spelled out at length what he saw as the pros and cons of putting Holmes on the Supreme Court. Roosevelt’s account reveals the qualities that he was looking for in a justice.

Among Roosevelt’s arguments for Holmes:

“He possesses the high character and the high reputation both of which should if possible attach to any man who is to go upon the highest court of the entire civilized world…. The position of Chief Justice of Massachusetts is in itself a guarantee of the highest professional standing.”

“Holmes has behind him the kind of career and possesses the kind of personality which make a good American proud of him as a representative of our country. He has been a most gallant soldier, a most able and upright public servant, and in public and private life alike a citizen whom we like to think of as typical of the American character at its best.”

“The labor decisions which have been criticized by some of the big railroad men and other members of large corporations constitute to my mind a strong point in Judge Holmes’ favor…. I think it eminently desirable that our Supreme Court should show in unmistakable fashion their entire sympathy with all proper effort to secure the most favorable possible consideration for the men who most need that consideration.”

Even more revealing of Roosevelt’s thinking is his “word as to the other side”—actually, more than 500 words on his one large concern about Holmes. Roosevelt’s concern arose from a short speech that Holmes had given in Boston on February 4, 1901 at a ceremony to celebrate John Marshall Day, the 100th anniversary of the date on which John Marshall became chief justice. In that speech, Holmes was somewhat stinting in his praise of Marshall. Marshall, he said, benefited from the good fortune of being in the right place at the right time. Holmes doubted whether Marshall’s work displayed “more than a strong intellect, a good style, personal ascendancy in his court, courage, justice, and the convictions of his party.” Admirable as some of those qualities are, the highest praise for judges, Holmes suggested, belongs to the “originators of transforming thought.” (He surely had himself in mind.)

Roosevelt was concerned that Holmes was undervaluing or even denigrating what it meant for Marshall to be faithful to the “convictions of his party.” It is essential, Roosevelt argued, that a justice be a “party man, a constructive statesman” in the “higher sense” of those concepts:

It may seem to be, but it is not really, a small matter that his [Holmes’s] speech on Marshall should be unworthy of the subject, and above all should show a total incapacity to grasp what Marshall did. In the ordinary and low sense which we attach to the words “partisan” and “politician,” a judge of the Supreme Court should be neither. But in the higher sense, in the proper sense, he is not in my judgment fitted for the position unless he is a party man, a constructive statesman, constantly keeping in mind his adherence to the principles and policies under which this nation has been built up and in accordance with which it must go on; and keeping in mind also his relations with his fellow statesmen who in other b[r]anches of the government are striving in cooperation with him to advance the ends of government.

In the next two paragraphs, Roosevelt’s “higher sense” of what it means for a justice to be a “constructive statesman” suddenly descends into the question whether Holmes agrees with Roosevelt on every political matter that Roosevelt regards as important:

I should like to know that Judge Holmes was in entire sympathy with our views, that is with your views and mine and Judge Gray’s, for instance … before I would feel justified in appointing him…. I should hold myself as guilty of an irreparable wrong to the nation if I should put in his place any man who was not absolutely sane and sound on the great national policies for which we stand in public life.

Foremost among such matters was the question whether the residents of the newly acquired American territories of Puerto Rico and the Philippines should have the full rights of American citizens. Roosevelt was adamant that they should not, as was Lodge. The Court, in a series of rulings in 1901 in the so-called Insular Cases, had sharply divided 5 to 4 in favor of Roosevelt’s imperialist position, but the issue was not entirely settled. In his letter to Lodge, Roosevelt condemned the dissenters for their “reactionary folly [that] would have hampered well-nigh hopelessly [the American] people in doing efficient and honorable work for the national welfare, and for the welfare of the islands themselves, in Porto Rico and the Philippines.”

In sum, Roosevelt held a deeply political view of the role of Supreme Court justices. He could maintain, and perhaps even convince himself, that his view was political only in a “higher sense” of that term. But as his vigorous stance on the Insular Cases revealed, his view extended to all sorts of matters on which faithful Americans could have very different understandings of “the principles and policies under which this nation has been built up and in accordance with which it must go on.”

* * *

Roosevelt wasn’t shy about making sure that Holmes understood what he was expecting in a Supreme Court justice. In saying that he “should like to know that Judge Holmes was in entire sympathy with our views,” Roosevelt was asking Lodge to vet Holmes. In his letter to Lodge, he tells him: “If it becomes necessary you can show him [Holmes] this letter.”

Lodge was eager to assist Roosevelt. Indeed, he had told Roosevelt that his recommendation of Holmes was “assuming always that he is right on the Porto Rican cases[,] for without absolute assurance on that point I would not appoint any man.”

A week later, Lodge wrote back to Roosevelt:

I agree most profoundly with every word you say. I can put it to Holmes with absolute frankness & shall[,] for I would not appoint my best-beloved on that bench unless he held the position you describe. As soon as I have talked with him[,] I will wire you & if he is absolutely & wholly all right, entirely with us & not otherwise, I will tell him to go to Oyster Bay as you request.

On July 23, Lodge sent a telegram to Roosevelt. Presumably for reasons of confidentiality, the telegram did not mention Holmes by name, but (in the elliptical phrasing common to telegrams) confirmed that Holmes was “all right”:

Have seen him all right and as you wish he leaves by 10 AM train tomorrow for New-York will reach Oyster-Bay afternoon if not convenient to you to see him tomorrow wire him today….

Roosevelt and Holmes ended up having their secret meeting on July 25. Roosevelt wrote that same day to Lodge:

I saw Holmes and am entirely satisfied.

* * *

In February 1902, Roosevelt had launched his crusade as a trust-buster by directing Attorney General Philander Knox to sue to break up the Northern Securities Company. J.P. Morgan had formed Northern Securities to combine the ownership of two major competing railway companies. In 1904, the Supreme Court ruled, by a vote of 5 to 4, that the government’s challenge to Northern Securities was authorized by the 1890 Sherman Act. Justice Holmes wrote one dissent and joined another.

I am not going to try to parse the competing opinions in Northern Securities. Suffice it to say that Roosevelt was livid that Holmes would stand against his major domestic initiative and side, as Roosevelt saw it, with the railway barons. It’s difficult to imagine that Roosevelt made it past these opening sentences of Holmes’s dissent without tossing it to the ground in disgust:

Great cases, like hard cases, make bad law. For great cases are called great not by reason of their real importance in shaping the law of the future, but because of some accident of immediate overwhelming interest which appeals to the feelings and distorts the judgment. These immediate interests exercise a kind of hydraulic pressure which makes what previously was clear seem doubtful, and before which even well settled principles of law will bend.

In a letter to Lodge two years later, Roosevelt expressed his “bitter disappointment” with Holmes:

Nothing has been so strongly borne in on me concerning lawyers on the bench as that the nominal politics of the man has nothing to do with his actions on the bench. His real politics are all-important. [Roosevelt’s emphasis.]

From his antecedents, Holmes should have been an ideal man on the bench. As a matter of fact he has been a bitter disappointment, not because of any one decision but because of his general attitude.

* * *

One need not embrace Holmes as a model of good judging in order to recognize that Roosevelt’s criticisms of him badly miss the mark. It was Holmes’s dissent in Northern Securities that elicited Roosevelt’s slam that Holmes did not have the backbone of a banana. But what reason is there to think that lack of courage explained Holmes’s dissent? If anything, it took courage for Holmes disagree with the legality of Roosevelt’s challenge to Northern Securities.

The “general attitude” that Roosevelt complains of would appear to be the impartiality of a judge. Roosevelt imagined that Holmes’s labor decisions on the Massachusetts supreme court reflected his “entire sympathy” with workers, and he wanted Holmes to display “entire sympathy with [Roosevelt’s] views,” to be “absolutely sane and sound on the great national policies for which we stand in public life.” But as one perceptive commentator observed 75 years ago:

Probably, in their prenomination quizzes, neither the President nor [Lodge] went into the [antitrust] question at all. Lodge was interested mainly in the territorial issue, and here the candidate’s views were similar to his own both personally and judicially. Neither Lodge nor any other imperialist had ever any reason to quarrel with Holmes’s opinions in the insular cases with which he dealt. Roosevelt was worried about party regularity as well as imperialism, but was manifestly satisfied when Holmes said that he was not a Mugwump—that he disapproved of “independents” in politics. Being a politician he could not appreciate that Holmes the judge was not Holmes the Republican private citizen. So he was unhappy later not because he had been deceived but because he had not understood. He had only himself to blame.

Holmes, this same commentator notes, declared the whole matter “rather comic”:

Roosevelt “looked on my dissent to the Northern Securities Case as a political departure,” he wrote Sir Frederick Pollock in 1921, and offered an estimate of Roosevelt which demonstrated clearly that he understood “TR” far better than “TR” understood him. “He was very likeable, a big figure, a rather ordinary intellect, with extraordinary gifts, a shrewd and I think pretty unscrupulous politician.”

* * *

Presidents who don’t understand or appreciate that the craft of judging is distinct from politics will be disappointed when they appoint Supreme Court justices who do understand that distinction and who do their best to abide by it. Some presidents and their supporters will conclude that’s a large reason not to appoint such justices: “Let’s get our political hacks on the Court.” But the constitutionally sound conclusion is that presidents should develop and pursue a better understanding of what good judging consists of.

Democrats invariably appoint SC justices according to his or her politics. Republican Presidents try, and often fail, to nominate judges according to their actual adherence to the Constitution. This leaves conservatives at a great disadvantage. I love Scalia and Thomas but we're unlikely to see their kind again. Onward and downward.

Sounds like Henry II and Thomas Becket. Thomas tried to warn Henry. Apparently Holmes didn't make it clear to Roosevelt.