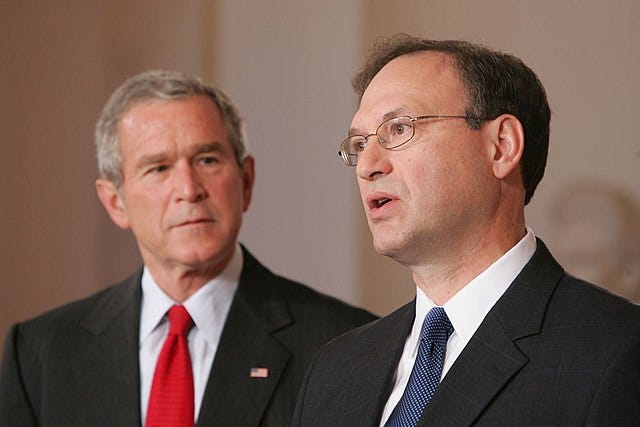

Pro-Lifers Try to Block Alito Nomination

And I thwart the foolish effort

If it sounds amazingly stupid now, I also found it amazingly stupid back then: In the immediate aftermath of the Harriet Miers debacle, a powerful pro-life group tried to block George W. Bush from nominating Samuel Alito to the Supreme Court.

In consultation with key White House officials and an important senator, I’m pleased to have helped to thwart the group’s terribly misguided effort.

* * *

My first, and so far only, trip to the Gettysburg battlefield was very memorable, but not at all in the way that I expected. On a Saturday morning two days after Harriet Miers’s Supreme Court nomination collapsed, I joined my son and his Cub Scout troop on a visit to Gettysburg.

I was riding in the front passenger seat of a car when I received a telephone call. President Bush was planning to nominate Third Circuit judge Samuel Alito to Justice Sandra Day O’Connor’s seat, I was told, but a surprising obstacle had arisen: a conservative activist group with a lot of clout on the issue of abortion was vehemently objecting to Alito.

I confess that I’m tempted to name the group. Doing so would avoid inadvertently casting misplaced aspersions on other groups that fit the same general description. Doing so would also enable me to add some amazing details, including an especially ironic twist regarding Justice Alito’s majority opinion 17 years later in Dobbs. I’d also draw a much larger audience for this post. But I don’t have any interest in reviving a very heated quarrel, so I am going to be oblique here in referring to the group. I will add that the group is one that I had worked with and admired.

When we got to Gettysburg, I spent the entirety of the several hours we were there in phone call after phone call on my BlackBerry, trying to figure out what the heck was going on. I learned that the group was troubled by Alito’s position in a 1995 case, Elizabeth Blackwell Health Center v. Knoll, involving Medicaid funding of abortion. But I couldn’t call up the case on my BlackBerry, so I had to wait until I got home to dig deeper.

* * *

I had carefully reviewed Alito’s 15-year record as a federal appellate judge and knew it to be outstanding. On the issue of abortion, Alito had two significant opinions, both of which struck me as sound.

In the Third Circuit’s decision in 1991 in Planned Parenthood v. Casey, the panel majority ruled that various provisions of Pennsylvania abortion law (for example, on informed consent and parental consent) were constitutionally permissible but it held that a spousal-notification provision was unconstitutional. Alito agreed with the panel majority on the provisions that it upheld, but explained in a separate opinion that he believed that the spousal-notification provision was also permissible. (On review, a five-justice majority of the Supreme Court disagreed with Alito as to the spousal-notification provision.)

In Planned Parenthood v. Farmer (2000), the panel majority, in an opinion by Judge Maryanne Trump Barry (Donald Trump’s sister), ruled that New Jersey’s ban on partial-birth abortion was unconstitutional. The panel issued its ruling one month after the Supreme Court’s decision in Stenberg v. Carhart ruled that Nebraska’s nearly identical law was unconstitutional. But for whatever reason, instead of simply holding that Stenberg compelled the same result, the panel majority issued a lengthy opinion that it explained “was in final form” before the Court heard oral argument in Stenberg. Alito concurred in the judgment on the ground that a lower court is obligated “to follow and apply controlling Supreme Court precedent,” but he declined to join Barry’s opinion, which he said “was never necessary and is now obsolete.”

Over the previous year, Alito had been prominently mentioned as a leading candidate for a Supreme Court nomination. So if any pro-lifers had concerns about his record on abortion, they had plenty of opportunities to air them. But now, out of the blue, this group was suddenly objecting to Alito on the basis of a ruling that neither it nor (so far as I could tell) anyone else in the pro-life community had raised against him before.

* * *

When I got home and read Elizabeth Blackwell Health Center v. Knoll, I quickly determined that the group’s concerns were ill-founded. The issue in the case was whether Pennsylvania’s reporting and physician-certification requirements for Medicaid-funded abortions complied with federal law. The majority opinion, which Alito joined, held that they did not. The dissent held that they did. But the divide between the majority and the dissent turned entirely on a threshold question of administrative law—did so-called Chevron deference apply to the Department of Health and Human Services’ interpretation of federal law?—that had nothing to do with abortion.

Alito provided the decisive vote on the panel against the pro-life position in the case. But he did so for the good reason that he understood that to be the correct legal conclusion.

As I wrote in an email that Saturday evening that was transmitted to the group’s leaders:

The divide between the majority and the dissent is on a pure question of administrative law. Alito is exactly where Scalia is on this question. So anyone who concludes that the opinion somehow is a serious strike against Alito ought to also dislike Scalia.

On Sunday morning, I was put in touch with White House deputy chief of staff Karl Rove, who (if I’m recalling the sequence of events correctly) informed me that the group was trying to enlist Senator Rick Santorum, the pro-life champion from Pennsylvania, against Alito. I spoke with Santorum and explained my understanding of the case to him. I was relieved to learn that he saw things clearly and was strongly supportive of Alito.

But by mid-afternoon, I still hadn’t heard back from the group’s leaders. I prodded them to tell me if they still had concerns. I then received a telephone call from their lawyer, who explained (and repeated in an email) that the group “want[s] judges who share pro-life values.” I responded that I understood that to mean that the group wanted justices who would indulge pro-life preferences in deciding cases, and I pointed out that Scalia would not meet that standard. Our exchange ended rather contentiously.

* * *

President Bush announced Alito’s nomination the following morning, Monday, October 31. In one of my first posts on the nomination, I undertook to preempt possible pro-life criticism of his vote in the Elizabeth Blackwell Health Center case. My post concluded:

There is no basis for inferring from this case anything about how Alito would approach other cases involving abortion—other than that Alito would apply the law neutrally and not indulge his own policy preferences (whatever they might be). That is exactly what everyone should want in a Supreme Court justice.

It is tempting, of course, for those of us strongly opposed to abortion to want justices who will have pro-life values and will indulge those values in their decisionmaking. But that is not what proper judging is about, and seeking such justices would be a foolish strategy. The idea that justices may properly impose their own values and policy preferences is precisely what produced cases like Roe. Moreover, given the strong likelihood that the legal elites will always be to the left of the American people, any efforts to legitimate or excuse that illegitimate idea will help to produce similar usurpations in the future.

I don’t think I ever heard about the case again, either from the group that tried to stop Alito’s nomination over it or from anyone else.

* * *

Although it did not cross my mind at the time, I now suspect that the group did not really find Alito’s position in the Elizabeth Blackwell Health Center case to be objectionable but that it (or its lawyer) was instead trying to advance the prospects of another candidate by damaging Alito’s. Whether or not that is what the group was doing, the tactic of unfairly disparaging a rival candidate is all too common.

That tactic, besides being dishonest, is also almost always foolish. No one on the outside can know where the thinking of the president and his top advisers sits at any particular moment. Maybe damaging the candidate in the lead will help the alternative candidate you favor, but maybe your alternative has already been eliminated and you’ll instead end up with a third candidate whom you regard as markedly inferior to the first.

The best course in my judgment—the course I have always tried to follow—is to distinguish between welcome and unwelcome candidates, to make sure that any comparative assessments you offer of the welcome candidates are well informed, and to trust the White House to make a good choice among the welcome candidates.

This is fascinating. The inclusion of the "offending" case decision is much appreciated.

It WAS 20 years ago. I think whatever the statute of limitations is on "giant boneheaded mistakes" has passed. Let he who has made no giant boneheaded mistakes since 2006 cast the first stone.

But I really want to know the "especially ironic twist"! (I'm thnking now that maybe Alito cited this group's work in the majority?)