Neil Gorsuch's Easy Path to Tenth Circuit

The power of a positive blue slip

When George W. Bush nominated him to the Tenth Circuit in May 2006, Neil Gorsuch had lots of the markings that had aroused vigorous Democratic opposition to Bush’s earlier appellate nominees. He had elite credentials. He had a strong conservative pedigree. And he was young—only 38. In short, Gorsuch had the profile of someone who, if confirmed to an appellate seat, would be a prominent contender for a Supreme Court nomination by a Republican president at some point over the next fifteen years.

Yet Senate Democrats allowed Gorsuch’s nomination to be confirmed by voice vote barely two months later.

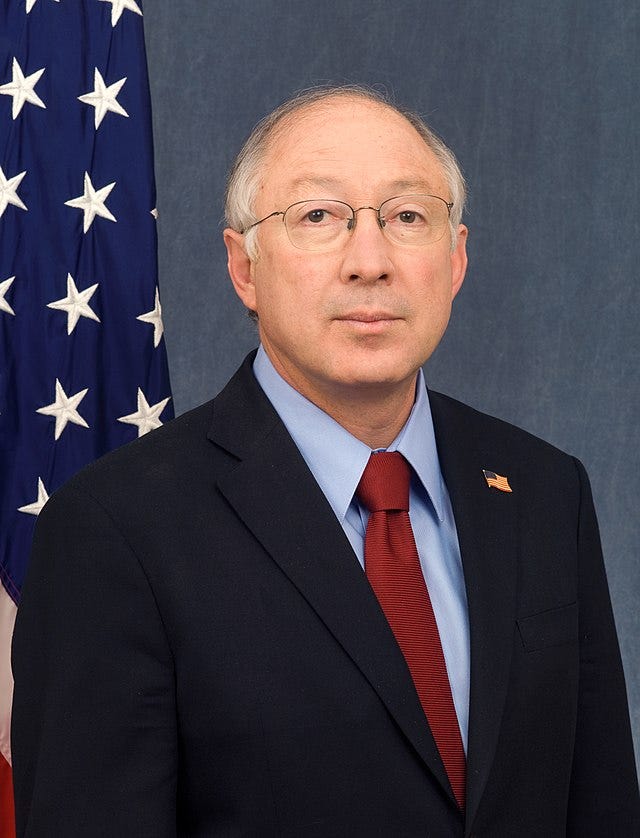

Gorsuch’s quick path to a very easy confirmation is an extraordinary testament to the power of a positive blue slip from an opposite-party senator: in his case, from Colorado’s Democratic senator Ken Salazar.

Eleven years later, Democrats would have ample reason to regret that they hadn’t mustered more of a fight over Gorsuch’s nomination.

***

Neil Gorsuch combined deep roots in Colorado with strong connections in D.C. A fourth-generation Coloradan, he spent his early years in Denver but moved with his family to the Washington, D.C. area when Ronald Reagan appointed his mother Anne Gorsuch Burford as Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency in 1981.

Gorsuch attended high school at Georgetown Prep—two classes behind Brett Kavanaugh—college at Columbia, and law school at Harvard, where he was an active member of the Federalist Society. He attended Oxford University as a Marshall Scholar and earned a Ph.D. under natural-law philosopher John Finnis.

Gorsuch clerked first for the conservative D.C. Circuit judge David Sentelle and then at the Supreme Court: on top of his primary clerkship with retired Supreme Court justice Byron White, he doubled up in Justice Anthony Kennedy’s chambers (along with Kavanaugh). Gorsuch joined the fledgling Kellogg Huber law firm (now known in full as Kellogg, Hansen, Todd, Figel & Frederick) in 1995 and soon became a partner in the firm.

In the spring of 2005, Gorsuch decided to take a break from private practice to become a senior official—principal deputy to the Associate Attorney General—in the Department of Justice.

At the end of 2005, an unexpected opportunity suddenly arose. Tenth Circuit judge David Ebel, whose chambers were in Denver, announced that he would take senior status in mid-January 2006. Reagan had appointed Ebel to his seat in 1988. In a curious twist, Ebel had been a law clerk for Justice White nearly thirty years before Gorsuch was.

***

The blue-slip privilege of home-state senators over appellate nominations was robust back in 2006. (It wasn’t demoted until late 2017.) Under the Senate Judiciary Committee’s longstanding practice, its chairman would invite home-state senators of both parties to express their approval or disapproval of each home-state judicial nominee on a sheet of paper (originally blue) that they would return to him. For Arlen Specter, the Republican chairman of the committee in 2005 and 2006, a negative or unreturned blue slip, even from a Democrat, would kill a nomination.

Colorado’s senators were Wayne Allard, a conservative Republican, and Ken Salazar, a moderate Democrat. Allard and Salazar each had a favorite candidate to replace Ebel, but Allard’s candidate wasn’t acceptable to Salazar, and vice versa. The Bush administration’s judicial-nominations team, which included lawyers from the White House and the Department of Justice, was eager to find a candidate whom Allard and Salazar would both accept, and it approached Gorsuch to see whether he would be interested.

Gorsuch wouldn’t want to be nominated unless Allard and Salazar would return positive blue slips on his nomination. After he met separately with them, they signaled that they would welcome his nomination.

On May 10, 2006, Bush formally nominated Gorsuch. Six weeks later, his confirmation hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee took place. The American Bar Association judicial-selection panel had unanimously given Gorsuch its highest rating of well-qualified, and the hearing was a very tame affair. No Democrats attended, and the only senator to pose any questions to Gorsuch was Republican senator Lindsey Graham. Graham tossed Gorsuch a half-dozen softballs, and the hearing was over in a matter of minutes.

On July 20, 2006, the Senate confirmed Gorsuch’s nomination by voice vote. Every Democratic senator waived the right to a roll-call vote both on cloture and on the nomination itself.

***

Why didn’t liberal Democrats put up more of a fight over Gorsuch’s nomination? The most likely answer is that they saw no upside to a fight that they knew they would lose.

Salazar’s positive blue slip guaranteed that Gorsuch would be confirmed. The Gang of 14 Agreement that had a year earlier removed the threat of a Democratic filibuster except “under extraordinary circumstances.” Salazar himself was one of the seven Democratic signatories to the Agreement. There was no realistic prospect that the other Democratic signatories to the Agreement would find that Gorsuch’s nomination presented “extraordinary circumstances.”

Recall that the signatories to the Gang of 14 Agreement had expressly agreed to support cloture on the nomination of William Pryor to the Eleventh Circuit. Pryor had shocked Senate Democrats with his candid testimony that he regarded Roe v. Wade as a constitutional “abomination” that had “led to the slaughter of millions of innocent unborn children,” and Bush’s recess appointment of Pryor in early 2004 had given Democrats further reason to oppose his confirmation. Having concluded that Pryor’s nomination did not itself present “extraordinary circumstances,” the Democratic signatories would certainly not object to Gorsuch.

If Chuck Schumer and other fervent opponents of Bush’s judicial nominees had fought against the Gorsuch nomination or even demanded a roll-call vote on it, they would have invited attacks by left-wing groups on their Democratic colleagues who voted for Gorsuch. Better—or so it seemed—just to surrender.

***

On January 31, 2017, Donald Trump announced that he would nominate Neil Gorsuch to fill the Supreme Court vacancy resulting from Antonin Scalia’s death. In touting Gorsuch’s qualifications, Trump highlighted that Gorsuch “was confirmed by the Senate unanimously” to his Tenth Circuit seat. Other news reports and analyses (including my same-night National Review essay) noted the same fact.

When Senate Democrats made their momentously foolish decision to filibuster Gorsuch’s Supreme Court nomination, the three Republican signatories to the Gang of 14 Agreement who were still in the Senate—John McCain, Susan Collins, and Lindsey Graham—all realized that if the Democrats were going to filibuster Gorsuch, they would filibuster anyone Trump nominated. As they saw it, nothing in Gorsuch’s record on the Tenth Circuit could explain why the same Democrats who allowed him to be confirmed by voice vote in 2006 would now pull out all stops to defeat him. In the opening of her speech objecting to the Democratic filibuster threat, Collins remarked that the Senate in 2006 had “confirmed this outstanding nominee by a voice vote to his current position on the U.S. Court of Appeals” and that a “rollcall vote was neither requested nor required.”

In 2005, the Gang of 14 Agreement had thwarted the Republican effort to abolish the filibuster on judicial nominations. In 2013 (as I will discuss in much greater detail), Democrats had abolished the filibuster for lower-court nominations but left it available for Supreme Court nominations. McCain, Collins, and Graham concluded that they had no choice but to finish off the project they had steadfastly resisted in 2005, and they provided the critical votes needed in the 52-48 vote to abolish the filibuster for Supreme Court nominations.

I am not contending that Republicans would have failed to overcome the filibuster of Gorsuch’s Supreme Court confirmation if Democrats had voted in significant numbers against his Tenth Circuit nomination in 2006. But I do believe that Democrats’ agreement to allow his Tenth Circuit nomination to be confirmed by voice vote helped to create an atmosphere that made their filibuster in 2017 appear all the more extreme.