Judicial Retirements and Judicial Vacancies

Exploring the Rule of 80

Like a shoal in a river, the federal statute that governs judicial retirements—28 U.S.C. § 371—is an inconspicuous feature that plays a major role in directing the flow of judicial vacancies. You can’t skillfully navigate your way if you don’t pay close attention to it.

Every White House is going to keep a careful list of which judges are, or soon will be, eligible to retire under section 371. The judges on that list are a promising source of new vacancies. That is especially true of those judges who were appointed by a president of the same party as the current president.

* * *

In addition to the nine Supreme Court seats, there are currently 179 authorized judicial positions on the federal courts of appeals and 663 permanent positions on the district courts. (I exclude from this discussion the ten existing “temporary” district judgeships; each expires when the incumbent leaves the position, so they do not give rise to new vacancies.)

Vacancies in these positions sometimes arise involuntarily—by the death of the judge while in “regular active service” or by his removal after impeachment by the House of Representatives and conviction by the Senate. (Over the past four decades, four district judges have been removed by impeachment and conviction, and a fifth resigned in the face of impeachment articles.)

Much more often, vacancies arise because judges choose to leave their positions. This is where section 371 comes into play. If we set aside the instances in which a judge accepts a new position in the federal judiciary (e.g., a district judge is elevated to a court of appeals), a judge who wants to leave his position has a choice among three options:

Resign before qualifying for a judicial pension

Fully retire with a judicial pension

Retire from regular active service but continue to serve in “senior status”

To qualify for either of the retirement options, section 371 imposes what is commonly known as the Rule of 80: The judge’s age in years plus his years of federal judicial service (in Article III life-tenured positions) must equal 80 or higher. Plus, he must be at least 65 and must have at least 10 years of federal judicial service. Fractional years don’t count.

Under section 371, a judge who meets the Rule of 80, if he chooses to fully retire (“retire from the office”), “shall, during the remainder of his lifetime, receive an annuity equal to the salary he was receiving at the time he retired.” (For 2023, the salary for appellate judges is $246,600 and for district judges is $232,600.)

Alternatively, a judge who meets the Rule of 80 may choose to “retain the office but retire from regular active service”—i.e., take senior status. If he makes that choice, he shall “continue to receive the salary of the office” if he satisfies the minimal workload requirement that section 371(e) prescribes—basically, 25% of the workload of a judge in regular active service. (Section 371 applies equally to Supreme Court justices; that’s how, for example, Justice Souter after retiring from the Court has sat on First Circuit panels.)

A judge who initially decides to take senior status may at any later time decide to fully retire. And, of course, a judge who meets the Rule of 80—a “senior-eligible” judge—may also choose to continue in regular active service for the time being and defer the decision between the retirement options.

A judge who resigns from the federal judiciary before meeting the Rule of 80 does not qualify for any judicial pension, no matter how old he is and no matter how many years he has served.

* * *

In considering the competing incentives faced by a judge who meets the Rule of 80, let’s start with the economic incentives.

Under section 371, a judge who fully retires shall “receive an annuity equal to the salary he was receiving at the time he retired.” While the salary of a judge in active service is subject to FICA (Social Security and Medicare) taxes, a judge’s retirement annuity is not. More importantly, a judge who has retired is free to take another job—which, depending on the judge’s abilities and reputation, could be a quite lucrative one. The comparatively modest downside of fully retiring is that the amount of the judge’s retirement annuity is fixed at the time he retires. He does not benefit from any salary increases, including the annual cost-of-living increases that judges receive. (Over time, those cost-of-living increases can accumulate to a significant amount: Judicial salaries in 2023 are about $60,000 higher than they were in 2014.)

Under section 371, a judge who takes senior status “shall continue to receive the salary of the office,” so he, like a judge who remains in active service and unlike a judge who fully retires, benefits from ongoing salary increases. But while a senior judge receives the same salary as an active-service judge, his after-tax compensation is some $10,000 or more higher. That’s because federal law exempts a senior judge from paying FICA taxes on his salary. (See 26 U.S.C. § 3121(i)(5) and 42 U.S.C. § 409(h).)

(At 2023 salaries, total FICA taxes come to around $13,600 for district judges and nearly $14,000 for appellate judges. A senior judge who does not have to pay those taxes has a correspondingly higher net income on which he must pay federal income tax.)

Some states even exempt a senior judge’s salary and a fully retired judge’s annuity from state income tax, so the benefit of taking senior status or fully retiring is even larger in those states.

In brief, a senior-eligible judge does not have any economic incentive to remain in regular active service. As a matter of mere economics, his incentive is to fully retire rather than to take senior status if he expects that the outside income he would earn would exceed the modest increases in judicial salary that he would be forgoing.

* * *

Most people who become federal judges don’t do so for economic reasons, and most judges who satisfy the Rule of 80 won’t rely heavily on economic reasons in deciding whether to stay in active status, go senior, or retire fully.

Let’s consider some of the reasons that a judge might decide to stay in active status.

A judge might remain in active status if he is concerned that the president will replace him with a successor of a very different ideology. One recent study concludes that “judges eligible to take senior status are today—more than ever before—deciding to do so in a politically strategic manner.”

On appellate panels, the judge in active status with the most seniority presides over oral argument, leads the discussion at conference, and assigns opinions. (A circuit’s chief judge is always deemed to have the most seniority.) An appellate judge who meets the Rule of 80 is likely to be the presiding judge on most of the panels on which he sits and, after years in which he was much more often a junior member of a panel, might be reluctant to give up the influence of that position.

For appellate judges, another reason to prefer active status is to be able to take part fully in the court’s en banc deliberations. Circuit rules and practices vary—from little to none—on the role that senior judges can play in en banc matters.

This en banc consideration is intensified if the judge worries that the appointment of his successor might have the effect, immediately or eventually, of tipping the balance of the court in the other direction. A judge who has this concern will be inclined to defer a decision to take senior status or to retire until a more simpatico president is in office.

Conversely, this en banc consideration is diluted if a judge is confident that the president will replace him with a successor of a similar ideology. If the judge takes senior status and his successor is appointed, the overall composition of the court (active judges plus senior judges) will weigh slightly more in his direction. If he fully retires and his successor is appointed, the overall composition of the court will be unchanged. Under either decision, he will not have to fear that his sudden death will give a later president the opportunity to swing the court in the other direction.

Similar ideological concerns might come into play for district judges, but because they act singly rather than en banc or (except very rarely) in three-judge panels, these concerns are likely to be more remote.

In an article on senior status, senior federal judge Frederic Block speculates that there are also some judges who are “psychologically challenged” to remain in active status:

There are those who simply have a difficult time accepting the label ‘senior’ as compared to ‘active.’ … These judges somehow feel that they will become lesser judges.

Relatedly, a judge might fear that by taking senior status he will become less attractive to future law clerks or be perceived by others as being in decline.

A judge who takes senior status can continue to carry a full caseload. A judge who intends to retain a full caseload might decide to go senior in order to enable his seat to be filled, thus increasing his court’s overall capacity (and perhaps bolstering its composition in the judge’s ideological direction). But if a judge wants a reduced judicial workload, then taking senior status is the obvious option. If he wants to stop doing judicial work altogether, then full retirement makes sense.

* * *

We have already seen a couple of instances of the Rule of 80 in operation.

When Bill Clinton made the controversial nomination of Lee Sarokin to a Third Circuit seat in May 1994, Sarokin was already 65 and was only six months away from having 15 years of service. Not much more than a year after his contentious confirmation, Sarokin stated his intention to take senior status. But when the Third Circuit denied his “highly unusual” request for permission to move his chambers from Newark to San Diego, he instead opted for full retirement. (In my previous post, I wrongly assumed that Sarokin’s pension annuity benefited from annual cost-of-living increases. I have corrected my error.)

Abner Mikva retired from the D.C. Circuit in September 1994 in order to become White House counsel for Bill Clinton. Mikva was 68 in 1994 and had just shy of 15 years of service on the D.C. Circuit, so he had satisfied the Rule of 80 (68+14=82) and was essentially working for free as a judge. So his incentive to jump directly back into the world of politics was reinforced by the fact that he had secured his judicial pension and would effectively be receiving a second salary. It is much less likely that he would have taken the White House position if he hadn’t already met the Rule of 80.

* * *

The judicial-retirement rules also affect the decisions of younger judges to resign. Consider the recent resignations of Fifth Circuit judge Gregg Costa and Ninth Circuit judge Patrick Watford.

Costa became a district judge at age 39 and a Fifth Circuit judge just before he turned 42. After eight years on the Fifth Circuit, he resigned in 2022 at the age of 50. Instead of working 15 more years to qualify for a judicial pension, he signed on as co-chair of Gibson Dunn’s Trials Practice Group. He will probably earn more in a year or two than he would in a decade or two of federal judicial annuities.

Ditto for Watford. He joined the Ninth Circuit in 2012 at the age of 44, and he resigned from that court earlier this year. Had he stayed on the court, he would not qualify for his judicial pension until he turned 65. Back in private practice at age 55, he will earn many, many millions of dollars in the coming decade.

Another prominent example is J. Michael Luttig. Luttig became a Fourth Circuit judge in 1991 at the age of 37. He was a runner-up for the Supreme Court vacancies that arose in 2005. In May 2006, just shy of turning 52, he resigned from the bench in order to become general counsel of Boeing. He would not have qualified for his judicial pension until he turned 65 in 2019. He earned many millions of dollars each year in his 13 years with Boeing.

For a somewhat different example, take David Levi, who became a federal district judge at the age of 39 and served in that position for 17 years before becoming dean of Duke law school at the age of 56.

In brief, many judges who take the bench at a young age will discover that they can parlay their reputations as judges into much higher paying, more prestigious, or more satisfying positions. Once they decide that they don’t want to remain on the bench, there is no reason for them to hang on for years to meet the Rule of 80.

* * *

Senior judges and judges who have chosen to remain in active status after satisfying the Rule of 80 could fully retire with a comfortable annuity and the opportunity for outside income. Instead, they are basically working for peanuts—for the annual cost-of-living increases they receive and for whatever hope they might have for a general salary increase. Whatever misgivings any of us might have about particular judges, there can be no doubt that in the aggregate these senior and senior-eligible judges play an invaluable role in the federal judiciary.

To illustrate: According to the Federal Judicial Center database, as of late August there were 172 appellate judges in regular active service. Of those 172, 40 were senior-eligible.* In addition, there were 127 appellate judges in senior status. On the conservative assumption that the average appellate judge in senior status is carrying a workload that is one-third of what an active judge carries, that would mean that senior-eligible judges and senior judges together account for well over one-third of the appellate workload. (The percentage might be even higher for district judges—late-August data showed 614 judges in regular active service and 486 senior judges—but I don’t know how many of the judges in regular active service are senior-eligible or the average load that a senior district judge carries.)

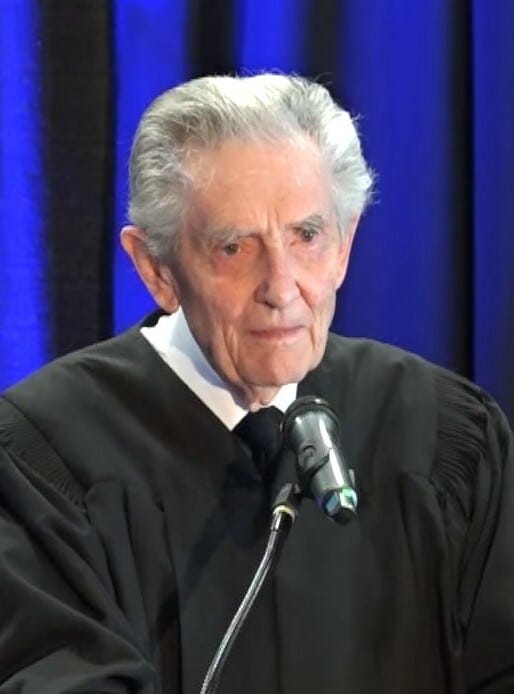

I will highlight for special recognition the two longest-serving federal judges on the bench today. Judge J. Clifford Wallace (for whom I clerked) and Judge Gerald Tjoflat were appointed to federal district court seats (in California and Florida, respectively) on the same day (October 16, 1970) more than five decades ago. Wallace was elevated to the Ninth Circuit in 1972 and Tjoflat to the Fifth Circuit in 1975. (Tjoflat became an Eleventh Circuit judge when the Eleventh Circuit was created out of the Fifth Circuit in 1981.) Wallace took senior status in 1996. Tjoflat continued in regular active service all the way until 2019, taking senior status just before he turned 90.

* * *

Every White House hopes that senior-eligible judges will decide to take senior status or to retire fully, and White House lawyers and their allies might occasionally make subtle, or not-so-subtle, efforts to encourage such decisions. The number of vacancies that the president will have the opportunity to fill will depend heavily on these decisions.

* I’m grateful to Russell Wheeler of Brookings for sharing with me his working document that tracks when sitting appellate judges become senior-eligible.

Paul Cassell and Michael McConnell apparently decided that they preferred academia to the judiciary.

Judge Cassell resigned as a federal district judge to focus on his return to his teaching career at the University of Utah.

Judge McConnell resigned from the Tenth Circuit to teach law at Stanford.

Both were elevated to the bench from the Utah faculty.

Both resigned long before the Rule of 80 would have applied.