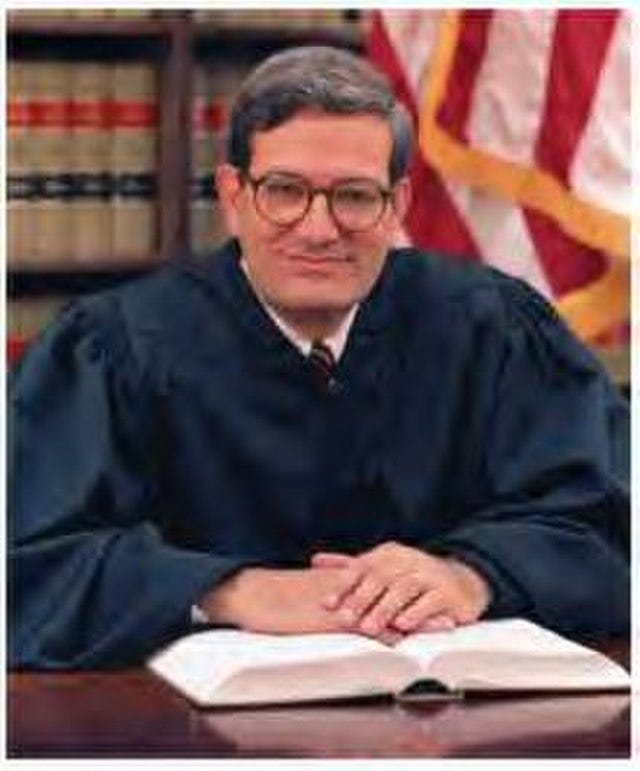

Judge José Cabranes Recounts His Supreme Court Candidacy

“If they kill me for the Supreme Court, they kill me for the Second Circuit”

So far I’ve been discussing the Supreme Court vacancy that arose in 1993 from my perspective as a Senate Judiciary Committee staffer for Senator Orrin Hatch. But it struck me that it might be interesting to get an inside view from the perspective of an actual candidate for the Supreme Court nomination. So I decided to reach out to Second Circuit judge José A. Cabranes, whose name was widely mentioned both for the 1993 vacancy to which Ruth Bader Ginsburg was appointed and for the 1994 vacancy to which Stephen Breyer was appointed.

It would be easy to understand that someone might not be very interested in talking about the unpleasant memory of missing out on a Supreme Court nomination. But in responding favorably to my inquiry, Judge Cabranes could not have been more gracious or more generous with his time.

Born in Puerto Rico, José Cabranes grew up in the Bronx and Queens, New York. He was one of two Hispanic students in his graduating class at Columbia College, and he went on to earn his law degree at Yale law school. After some years in private practice, he taught at Rutgers law school. (Ruth Bader Ginsburg chaired the committee that recruited him to Rutgers.) He was a founding member, and later chairman, of the Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund. In 1975, he became Yale University’s general counsel.

In 1979, Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan wanted Cabranes to take a federal district judgeship in the Southern District of New York. But President Jimmy Carter, at the urging of Senator Abe Ribicoff, instead appointed him to a seat in Connecticut. Cabranes was just 38 years old when he took the bench, and he was the first federal judge of Puerto Rican ancestry to be appointed to a seat outside Puerto Rico.

Over the ensuing dozen years, Cabranes distinguished himself on the district court and earned respect from both liberals and conservatives. When Justice Byron White announced in March 1993 that he would retire, President Bill Clinton would have found Cabranes an intriguing prospect. On top of Cabranes’s strong qualifications and his relative youth (52), Clinton would have relished appointing the first Hispanic Supreme Court justice. It’s therefore no surprise that Cabranes was immediately mentioned as a leading contender.

Clinton took a remarkable 86 days to select Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Judge Cabranes says he was amazed at Clinton’s delay and at his inability to make a decision: “I never understood why President Clinton didn’t immediately choose [Eighth Circuit judge] Richard Arnold, whom he knew well and rightly admired. It’s as if he didn’t trust his own judgment, even though he himself was a Yale law school graduate.”

For both the 1993 and 1994 vacancies, Judge Cabranes never had the impression that he would be the nominee, and he thought that he was in the mix “to add some spice or color to the whole process.” Ron Klain, who was then White House associate counsel, invited him on short notice for an interview at the White House: “Please get down here immediately.” But as Cabranes was preparing to head to the airport, a call came from the White House scrapping the interview. Cabranes soon heard that some feminist activists who were close to Hillary Clinton, including some who were friends of his, made clear that they would never find it acceptable for Bill Clinton to nominate Cabranes—who had the undesirable combination of being male, Hispanic, and Catholic.

Cabranes’s life didn’t change much during the selection process. He received frequent calls from a couple of reporters eager to inquire what he knew. One of the reporters, David Margolick of the New York Times, was writing a long profile of Cabranes in case Clinton selected him. When that didn’t happen, Cabranes quipped to Margolick that he was sorry Margolick’s diligent work would never end up in print. Margolick assured him that one day it would: “in your obituary.”

Among the unpleasant aspects of being talked about as a potential Supreme Court nominee, Judge Cabranes recalls that one nutty vexatious litigant whom he had sanctioned resurfaced and distributed “No way, José” campaign-style buttons. Also, when a local reporter told Cabranes that he knew there was a Michael Jordan fan in his household, Cabranes realized that the large poster of Michael Jordan in his elder son’s bedroom was visible from the street—at least with binoculars or a parfocal-lens camera.

One mischievous development complicated Cabranes’s candidacy in 1994. Yale law school dean Guido Calabresi informed colleagues that word was spreading among the liberal Hispanic groups supporting Cabranes’s candidacy that Cabranes’s daughter, as an aide to Vice President Dan Quayle, had written a memo assuring the George H.W. Bush White House that Cabranes was pro-life. The story was an utter fiction. But it alarmed Cabranes. It’s one thing to lose out on a Supreme Court nomination. It’s quite another to be damaged in the process. Cabranes worried that “if they kill me for the Supreme Court, they kill me for the Second Circuit.”

Supreme Court candidates in recent years have benefited from the support of former law clerks and other allies to make the case for them and to rebut criticisms. Things were much simpler back in 1993 and 1994. Judge Cabranes recalls hearing from a former law clerk that law clerks of Judge Arnold were circulating a paper touting his record, especially in environmental cases. Cabranes was being widely described as a “moderate”—a label that didn’t particularly help him—and his former clerk wanted to know if she should mobilize an effort to show that he was more liberal than depicted. Cabranes declined the assistance.

* * *

When Bill Clinton became president in 1993, Judge Cabranes’s great hope was to be elevated to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. Second Circuit judge Thomas Meskill, who had chambers in Connecticut, mentioned to Cabranes that he would be taking senior status when he turned 65 in July 1993. Cabranes was an obvious candidate to fill that seat, and he quickly garnered the critical support of Connecticut’s two Democratic senators, Chris Dodd and Joe Lieberman.

But in an ironic twist, the repeated mentions of Cabranes as a candidate to replace Justice White derailed his potential nomination to the Second Circuit seat in Connecticut. For nearly three months, Clinton dithered and dallied in picking White’s replacement. Cabranes had the strong support of Hispanic groups. If the White House went forward on the preliminary steps (e.g., FBI review) to nominate Cabranes to the Second Circuit before Clinton made his Supreme Court pick, it would be clearly signaling that Clinton wouldn’t be nominating Cabranes to replace White. Such a signal, before Clinton settled on his nominee, would easily be perceived by the Hispanic groups as slighting them.

As Cabranes put it to me, “Politics abhors a vacuum.” With his Second Circuit nomination in limbo, a new name surfaced for the seat: Yale law school dean Guido Calabresi, who was 60 years old. In his recently published oral history, Calabresi says he “was worried that the administration only wanted to appoint him in order to block [Cabranes’s] nomination.” But once Bill Clinton assured him that he admired Calabresi (“it was clear that he wanted me,” Calabresi recalls), Calabresi was happy to take the seat.

Federal appellate seats are not formally assigned by state, but senators, eager to preserve their patronage opportunities, ensure that seats come to be identified by state. Cabranes had lost out on the Connecticut seat that had opened up, and no other vacancy in a Connecticut seat could be expected to arise for several years, so Cabranes’s chance to be elevated to the Second Circuit seemed to have been lost. But Cabranes’s wife (a Yale law school professor) and his mother (living in Puerto Rico) saw things differently. When Cabranes mentioned to them that a New York vacancy on the Second Circuit had arisen, each responded, “You’re a New Yorker!”

Cabranes proceeded to contact Senator Moynihan about the putative New York seat. In a remarkable sign of his admiration for Cabranes, Moynihan, the Democratic senator from New York, agreed to support Cabranes for the New York seat, even though Cabranes would have his chambers in New Haven, Connecticut. The White House came on board, and everything seemed in place.

Until, that is, Justice Harry Blackmun announced his retirement from the Court in April 1994. “Oh, s***!,” Cabranes said to himself, as he contemplated having a Second Circuit nomination slip away from him again while his purported candidacy for the Supreme Court vacancy lingered.

Clinton announced on May 13, 1994, that he would nominate Stephen Breyer to fill Blackmun’s vacancy. Earlier that day, White House counsel Lloyd Cutler called Cabranes to assure him that he would be nominated to fill the New York opening on the Second Circuit. Eleven days later, Clinton announced that nomination. Cabranes expressed to me his gratitude to Senator Hatch for helping him secure a prompt hearing. The Senate went on to confirm Cabranes’s nomination by voice vote, and he was sworn in as a Second Circuit judge in August 1994.

* * *

One further wrinkle to Judge Cabranes’s Second Circuit seat: Senator Moynihan made clear in 1994 that he was lending New York’s seat to Cabranes. When Cabranes informed the White House in 2021 that he would be taking senior status (upon confirmation of his successor), his letter to President Biden made clear that he had been occupying a New York seat. Yet in a surprising turn of events, several months later the two senators from Connecticut, Richard Blumenthal and Chris Murphy, announced that they would be considering candidates to replace Cabranes, and President Biden ended up nominating Connecticut supreme court justice Maria Araújo Kahn to replace Cabranes. The Senate confirmed Kahn’s nomination in March 2023, and she has established her chambers in New Haven.

How New York’s senators Chuck Schumer and Kirsten Gillibrand allowed this seat to stay in Connecticut is something of a mystery—all the more so given Schumer’s great clout as Senate majority leader. By Blumenthal’s account, he somehow persuaded Schumer that the seat belongs to Connecticut.