John Roberts’s Gay-Rights Surprise

A revelation that would have prevented his nomination doesn't disrupt it

The nomination process for a Supreme Court seat often yields unexpected new nuggets of information about a candidate. The same piece of information can have dramatically different impact depending on when it surfaces. A fact that is learned during the president’s selection process might doom or damage a candidate’s prospect of being nominated. The very same fact, if it is discovered after the successful launch of a nomination, might have little or no impact or might even help the nominee win confirmation.

John Roberts’s gay-rights surprise starkly illustrates the point.

* * *

George W. Bush announced on July 19, 2005 that he had selected John Roberts to fill the Supreme Court seat that Sandra Day O’Connor was vacating. The nomination quickly won broad and enthusiastic support among conservatives. Then, on August 4, the Los Angeles Times reported the very surprising news that a decade earlier Roberts had “worked behind the scenes for gay rights activists” in the case of Romer v. Evans (1996):

Then a lawyer specializing in appellate work, the conservative Roberts helped represent the gay rights activists as part of his law firm’s pro bono work. He did not write the legal briefs or argue the case before the high court, but he was instrumental in reviewing filings and preparing oral arguments, according to several lawyers intimately involved in the case.

Jean Dubofsky, who argued the case in the Supreme Court, described Roberts’s strategic advice as “absolutely crucial” in enabling her to navigate questions from conservative justices. She recounted that Walter Dellinger, a liberal scholar of constitutional law who held a senior position in Bill Clinton’s Justice Department (and who would soon become acting Solicitor General), had recommended that she enlist Roberts’s assistance.

Walter A. Smith, the lawyer in charge of pro bono matters at Roberts’s law firm, “said he had little trouble recruiting” Roberts to work on the case. Smith noted that the firm’s pro bono ethos certainly did not require Roberts to do so:

“Anyone who didn’t want to work on a case for whatever matter, they didn’t have to.”

The White House stated that Roberts “spent less than 10 hours on the case.”

The questionnaire that the Senate Judiciary Committee submitted to Roberts asked: “Describe what you have done to fulfill [pro bono] responsibilities, listing specific instances and the amount of time devoted to each.” In his response, Roberts did not mention Romer. He discussed in detail two cases in which he served as lead counsel, working “over 200 hours” in one and “over 110 hours” in the other. He added that he had helped other lawyers prepare for oral argument in “pro bono matters involving such issues as termination of parental rights, minority voting rights, noise pollution at the Grand Canyon, environmental protection of Glacier Bay, Alaska, and election law challenges.”

* * *

The legal issue in Romer was whether a Colorado constitutional amendment that prohibited the state legislature and cities from enacting special protections for gays and lesbians violated the federal Equal Protection Clause. Given the Court’s recent ruling in 1986 in Bowers v. Hardwick, which upheld a ban on homosexual sodomy, the answer should have been easy. Under Bowers, classifications on the basis of sexual orientation were subject only to deferential rational-basis review. The federal Constitution gives broad play to states to structure their lawmaking as they see fit. So just as the Colorado legislature and its cities could have declined to provide special protections for gays and lesbians, the citizens of Colorado could do so through the state constitution.

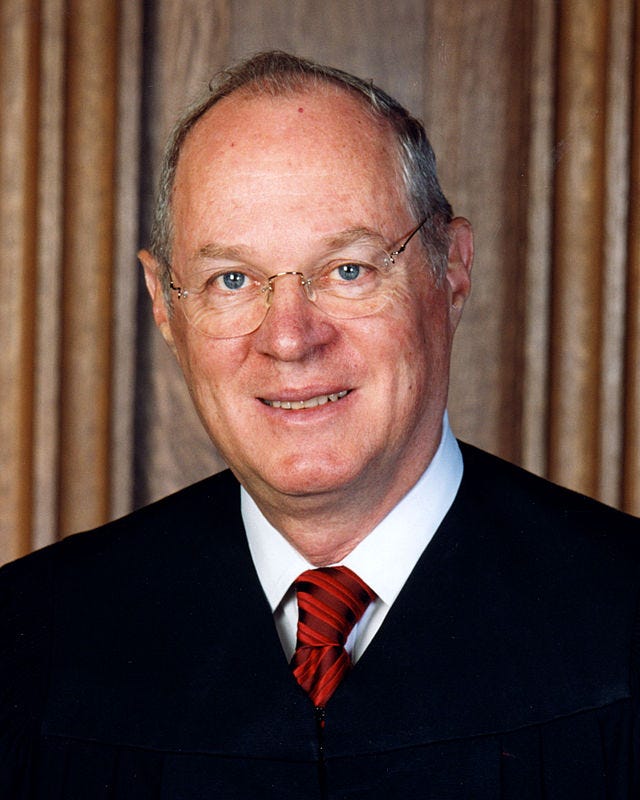

But in what “gay rights activists at the time described . . . as the movement’s most important victory,” the Court ruled by a vote of 6 to 3 that the Colorado constitutional amendment violated the federal Equal Protection Clause. I have tried several times over the years to make sense of Justice Anthony Kennedy’s majority opinion—to try to discern his reasoning, even if I don’t find it persuasive—and have never succeeded.

Astonishingly, Kennedy’s opinion in Romer did not even cite or acknowledge Bowers, much less try to distinguish it away. Yet seven years later, in his majority opinion in Lawrence v. Texas (2003) overruling Bowers, Kennedy would declare that the “foundations of Bowers have sustained serious erosion from our recent decisions in [Planned Parenthood v. Casey] and Romer.”

Kennedy’s opinion in Lawrence signaled that he and a majority of the Court were open to inventing a federal constitutional right to same-sex marriage. Several months later, the Massachusetts supreme court declared that the state constitution provided a right to same-sex marriage.

In July 2004, in the midst of his re-election campaign, George W. Bush announced his support for a federal constitutional amendment that would preserve marriage as a male-female union. On Election Day in 2004, voters in eleven states (including blue states Oregon and Michigan) adopted state constitutional amendments that enshrined marriage as a male-female union, all “by double-digit margins.”

Heavy turnout in Ohio in support of its constitutional amendment on marriage is widely credited with delivering Bush a narrow (2.1%) victory in that state. Ohio’s 20 electoral votes were decisive in the presidential election: had John Kerry won them, he would have been elected president.

* * *

If it had been known in advance of his selection that Roberts had volunteered his formidable legal skills in support of the gay-rights plaintiffs in Romer, I think that it is highly unlikely that Bush ever would have nominated him. Indeed, if that information had surfaced at Roberts’s 2003 confirmation hearing on his D.C. Circuit nomination, I don’t see how Roberts would ever have made it on a short list for the Supreme Court.

It wouldn’t have been difficult to disqualify Roberts from consideration. Bush’s powerful base of social conservatives would have united against Roberts for assisting the opposition on a matter of high consequence. Legal conservatives who saw Romer as a deeply unsound decision would not have inferred that Roberts agreed with the plaintiffs’ arguments in Romer. But most of them would never themselves have lent any support to the ideological cause of constitutionalizing gay rights. They would have taken Roberts’s involvement in Romer as validating concerns that he wasn’t a principled and courageous legal conservative. In the face of such opposition, and with so many other candidates available, Bush’s advisers would sensibly have seen fit not to explore Roberts any further.

* * *

The fact that the discovery of Roberts’s role in Romer came only after his nomination had been successfully launched changed everything.

I was a participant in daily coalition calls, and I can attest that the private response of many conservatives to the news ranged from disbelief to disappointment to despair. But the public response was much more muted. One national organization of conservative Christians slid past Smith’s acknowledgment that Roberts could simply have declined to take part in the matter, as it issued a statement that said: “That’s what lawyers do—represent their firm’s clients, whether they agree with what those clients stand for or not.” Another prominent social conservative tried to soothe concerns by asserting that those who were objecting simply didn’t know much about the “high degree of collegiality” in Supreme Court practice. Yet another leader charged that the disclosure was “a red herring meant to divide the right.” Many others just bit their tongues and tried to console themselves by focusing on other aspects of Roberts’s record.

Once everyone has already boarded the nomination ship and it has begun sailing to its destination, it’s not simply going to turn around and return to port. You can jump off the ship. But what will that achieve? Or you can try to organize a mutiny. But what are your prospects of success? And might you so severely damage the ship that, even if you could force it to return to port, it would be in bad shape for its next journey? The most sensible option is usually just to stay the course and hope for the best—and to work hard to avoid similar surprises on future nominations.

* * *

According to many folks who know him, John Roberts long aspired to be a Supreme Court justice and carefully calculated how best to achieve that ambition. I don’t mean this observation pejoratively. The same could be said of many current and recent justices and is probably much more the rule than the exception. You don’t usually get somewhere so special without setting it as your goal.

If my observation is correct, it’s interesting to speculate why Roberts risked imperiling his nomination prospects by volunteering to assist the plaintiffs in Romer. What if, say, the Senate questionnaire had unambiguously called for Roberts to list every pro bono matter on which he had worked?

One answer might be that Roberts miscalculated how consequential Romer would become—that he figured that it would be at most a one-off from Bowers, not a stepping stone to overturning Bowers and to inviting invention of a constitutional right to same-sex marriage.

Another, or an additional, answer might be that Roberts’s nomination to the D.C. Circuit in 1992 had been obstructed by Senate Democrats and Roberts wanted to find a way to overcome their obstruction of a future nomination. Walter Dellinger was very influential with Senate Democrats. Responding favorably to Jean Dubofsky’s request, made on his recommendation, would win points with him. Declining might lose points.

Another possibility is that Roberts figured that a general policy of helping out on any pro bono matter on which his assistance was requested would diminish the criticism that he might receive from conservatives. But would he conceivably have thought that if he had been asked to work on a pro-abortion cause?

In any event, in the end it would seem that Roberts didn’t miscalculate at all, as the discovery of his role in Romer came too late to damage his nomination and might even have helped him pick up votes from Democratic senators.

* * *

“Just who do we think we are?,” Chief Justice Roberts plaintively asked in his vehement dissent in Obergefell v. Hodges (2015) from the Court’s “extraordinary step of ordering every State to license and recognize same-sex marriage,” “an act of will, not legal judgment[, that] has no basis in the Constitution or the Court’s precedent.”

Who knows whether what Jean Dubofsky called Roberts’s “absolutely crucial” strategic advice in Romer required his vigorous dissent two decades later?

Thanks for this.

Seeing sausage being made may not make you “swear off” your fatty protein of fast-breaking preference. But it surely will be an explanatory experience when later in life you are looking back trying to figure out why your damned arteries are clogged.

So basically the GW Bush administration failed to do the basic research that would have uncovered Roberts's participation in Romer. If this research had been done before nominating him to the DC Circuit (or Scotus) then GW Bush would have nominated a real conservative(and hopefully not Luttig, who has turned into an imbecile over TDS) and we wouldn't have this Roberts albatross around the court's neck right now.

Seems like yet another great failure by GW Bush!