Introducing Confirmation Tales

“Not after I’ve driven all this way!”

In late June of 1991, I was driving cross-country from Los Angeles to Washington, D.C., in order to begin a one-year clerkship with Supreme Court justice Antonin Scalia. On the Blue Ridge Parkway in southwestern Virginia, I had only a few hours left to complete my trip. My car radio’s reception alternated from clear to static along the curvy mountain highway.

Suddenly I heard a news announcer declare: “In a surprising decision, a great Supreme Court justice has announced his retirement.”

“Oh, no!” I immediately said to myself, “not after I’ve driven all this way!”

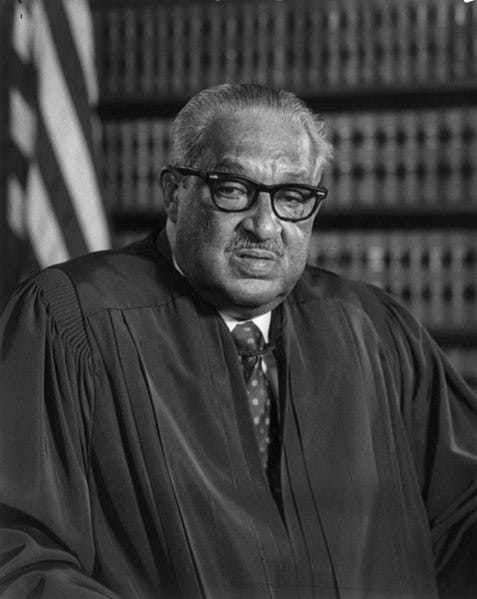

On a moment’s reflection, I took relief in realizing that the NPR reporter I was listening to would not yet have recognized, much less acknowledged, Justice Scalia’s emerging greatness. It was instead Thurgood Marshall who was retiring after more than two decades on the Court. “I’m getting old and coming apart!,” explained the great civil-rights litigator who in 1967 had become the first African-American justice.

Four days later, President George H.W. Bush nominated Clarence Thomas to fill Marshall’s seat. As a law clerk for Justice Scalia, I was a dazed bystander to the hearings that took place in the Senate office building just across Constitution Avenue in September and October, hearings that culminated in the Senate’s confirmation of Thomas by a vote of 52 to 48.

There have been ten Supreme Court vacancies and twelve Supreme Court nominees since then, and I have been immersed in all the confirmation battles: I was a lead Judiciary Committee staffer to Senator Orrin Hatch for the nominations of Ruth Bader Ginsburg in 1993 and Stephen G. Breyer in 1994. And for the other nominations, I have, in my work at the Ethics and Public Policy Center, been a blogger, commentator, sometime adviser, and, in one instance each, a mock senator in a White House moot-court session and a testifying witness at a confirmation hearing.

Like it or not, it’s a safe bet that over the past thirty years no one has studied the records of the Supreme Court nominees and of other leading contenders more comprehensively than I have, and no one has written more extensively about those records. (Here, as an example, is a collection of my writings on Justice Amy Coney Barrett’s nomination in 2020.) The same is true, I think, for lower-court nominees who have been in confirmation battles. In supporting many nominees and opposing lots of others, I’ve been engaged in the broader project of advancing judicial principles that I believe are faithful to the role of the courts under our Constitution.

For all that I have written about confirmation battles over Supreme Court and lower-court vacancies, I have a lot more to tell—stories and reflections that, I hope, will be interesting to readers across the ideological spectrum and that will also provide some important lessons and insights on such matters as: How has the judicial-confirmation process changed over recent decades? What factors—political, legal, technological, sociological, among them—have driven these changes? What role have good and bad strategic decisions, and plain old luck, played in the process? And what does all of this portend for future confirmation battles?

These stories and reflections will be the focus of this Confirmation Tales newsletter.

I will also continue to write regularly on current controversies over judicial matters at National Review Online’s Bench Memos blog. I invite readers who aren’t already doing so to follow my work there or to sign up for my free email distributions of my blog posts and other writings.