Harriet Miers's Nomination Collapses

Revisiting a harrowing 24 days in October 2005

Few episodes since Watergate have generated more intense and ugly conflict among Republicans than George W. Bush’s nomination of Harriet Miers to the Supreme Court in October 2005. The 24 days from announcement to withdrawal were excruciating for conservatives. Revisiting them has revived a lot of unpleasant memories. But it also provides the occasion to call attention to some important lessons.

(I do not undertake to provide a full history of the Miers nomination. Jan Crawford, in her excellent Supreme Conflict, devotes a 20-page chapter to the nomination. I read her book when it was first published in 2007 and have just reread the Miers chapter. I draw heavily here on contemporaneous newspaper articles, recent interviews I’ve conducted, and my own recollections, but I might owe more to Crawford’s account, even if indirectly, than I realize.)

* * *

It was late in the afternoon on the day of Bush’s announcement (October 3), I believe, that I called a friend in the White House to vent about the Miers selection. Having taken part in a conservative-coalition conference call and in countless phone calls and email exchanges, I wanted to make sure that the White House was aware that the hostile response of conservatives to the Miers nomination was much broader and stronger in private than it yet was in public.

My friend might well have told me that it was time for everyone to get on board. He instead responded, “Keep telling me what you’re hearing.” His response assured me that savvy folks in the White House already knew that the nomination was in deep trouble and might collapse.

* * *

A minimal standard of whether a Supreme Court nomination is a political success is whether it unifies the president’s party. By that standard, the Miers nomination was off to a terrible start.

Things got worse very quickly. The meet-and-greet meetings that Miers had with Republican senators on the Judiciary Committee went very poorly. Arlen Specter, chairman of the committee, stated after his meeting with Miers that she “needs a crash course in constitutional law.” Sam Brownback, a prominent social conservative, said that he would consider voting against her. Yet another Republican, one who the White House was especially hoping would come to Miers’s rescue, had such a frustrating experience that he instructed his staffer to tell the White House that he had no comment on the meeting. Tom Coburn, when asked by Miers how she had done in her interview with him, bluntly replied, “You flunked.”

Miers told Specter that former Chief Justice Warren Burger was her favorite justice. Stories circulated among Senate staffers that she confused Burger with his predecessor Earl Warren. One anecdote, perhaps apocryphal, is that when Specter asked her who her favorite justice was, she first responded “Warren” and then clarified that she meant Warren Burger. From a nominee of a president who had promised to select justices “in the mold of Scalia and Thomas,” neither Warren was a welcome response.

For senators, one important purpose that meet-and-greet meetings serve is that they enable senators to take a measure of the nominee, to make an early assessment of how appealing and effective the nominee is likely to be at the confirmation hearing. Republican senators didn’t want to incur the political cost of being caught in crossfire between the White House and conservative constituents opposing Miers. But Miers’s performance at the meet-and-greets told senators that her hearing testimony would intensify the crossfire.

The White House’s efforts to elicit public support from conservatives did not play out well. Evangelical leader James Dobson, head of Focus on the Family, explained that he supported Miers’s nomination because Karl Rove had privately told him (in the words of this New York Times article) “about her membership in a conservative evangelical church and her past support for an anti-abortion group in Texas” and had “assured him that Ms. Miers was the kind of conservative jurist that the president had promised to appoint.” Committee Democrats, in response, expressed an interest in having Dobson and Rove testify about their conversation.

Another evangelical leader, Pat Robertson, made a crude sectarian threat against any Republican senators who might vote against Miers:

Television evangelist Pat Robertson warned Republican senators not to vote against Miers, noting that most of them had voted for Ruth Bader Ginsburg -- whom Robertson described as a former American Civil Liberties Union lawyer -- when she was nominated by President Bill Clinton in 1993. “Now they’re going to turn against a Christian who is a conservative picked by a conservative president and they're going to vote against her for confirmation?” he asked on his show. “Not on your sweet life if they want to stay in office.” [Washington Post, Oct. 13, 2005]

* * *

The White House attacked Miers’s critics as “elitist,” as if their opposition were based on the law school she attended rather than the absence of a record that indicated that she would be an outstanding justice. The attack recalled Nebraska senator Roman Hruska’s infamous defense in 1970 of Richard Nixon’s Supreme Court nominee G. Harrold Carswell against charges that Carswell was a mediocrity:

Even if he [Carswell] were mediocre, there are a lot of mediocre judges and people and lawyers. They are entitled to a little representation, aren’t they? We can’t have all Brandeises and Frankfurters and Cardozos.

The attack particularly backfired with Arlen Specter, who regarded the Supreme Court as an elite institution that should be filled with justices with outstanding legal minds.

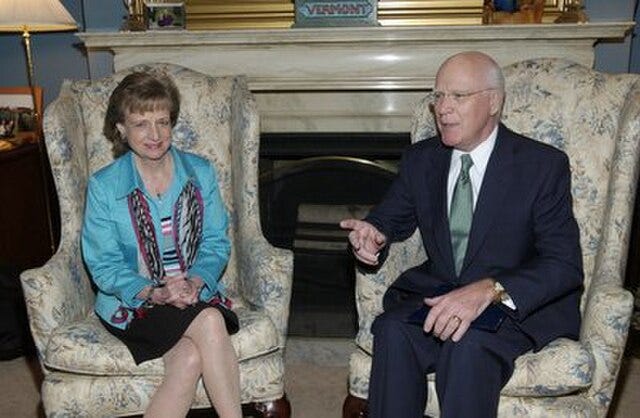

In an extraordinary slap, Specter and Patrick Leahy, the senior Democrat on the committee, held a press conference on October 19 at which they disclosed that they and other committee members had deemed parts of Miers’s response to the Senate questionnaire to be “inadequate,” “insufficient,” and “insulting.” They gave her a week to resubmit her response. As the New York Times noted, “Veteran senators and aides said they could not recall another occasion when the committee had sent back a nominee’s answers to a questionnaire because they were incomplete.” Specter also informed Miers that her hearing would begin 19 days later, on November 7.

* * *

Specter and Leahy also asked the White House to release various documents related to Miers’s work in the White House. In the meantime, Miers’s prep sessions for her hearing were going so poorly that White House officials concluded that her nomination needed to be withdrawn.

The committee’s request for White House documents gave the White House an exit ramp. On October 24, President Bush, invoking concerns of executive privilege, emphatically refused the request, calling it “a red line I’m not willing to cross.”

On October 27, Miers wrote Bush a letter withdrawing her nomination in order to protect “the prerogatives of the Executive Branch”:

As you know, members of the Senate have indicated their intention to seek documents about my service in the White House in order to judge whether to support me…. While I believe that my lengthy career provides sufficient evidence for consideration of my nomination, I am convinced the efforts to obtain Executive Branch materials and information will continue.

As I stated in my acceptance remarks in the Oval Office, the strength and independence of our three branches of government are critical to the continued success of this great nation. Repeatedly in the course of the process of confirmation for nominees for other positions, I have steadfastly maintained that the independence of the Executive Branch be preserved and its confidential documents and information not be released to further a confirmation process. I feel compelled to adhere to this position, especially related to my own nomination. Protection of the prerogatives of the Executive Branch and continued pursuit of my confirmation are in tension. I have decided that seeking my confirmation should yield.

* * *

It’s easy to disparage Harriet Miers. But it would be wrong to do so. Miers was a very accomplished lawyer who was thrust into a nomination for which she was ill-suited. She had very little familiarity with the legal issues that are the focus of a Supreme Court confirmation hearing. She had no time for the “crash course in constitutional law” that she needed. And she lacked the glibness that might conceal her shortcomings.

To be sure, Miers could have turned down the nomination in the first place. But how many lawyers would do so?

In the modern era of confirmation battles, a president takes a real risk in nominating as a Supreme Court justice someone who doesn’t have judicial experience, who isn’t well known by influential constituencies, and who hasn’t already demonstrated the ability to navigate a Senate confirmation process.

As George W. Bush concludes in his memoir (Decision Points), “I put my friend in an impossible situation.” Yes, he did.