George W. Bush's Dismal Failure on Fourth Circuit Nominations

How and why the conservative court shifted left

When George W. Bush became president in January 2001, the Fourth Circuit was widely regarded as the most conservative federal appellate court in the country. Bush seemed well positioned to entrench and expand the Fourth Circuit’s conservative majority: There were four vacancies on the fifteen-seat court, and a fifth seat, held by Bill Clinton’s recess appointee Roger Gregory, would expire in late 2001. So Bush, by appointing conservative judges to those five seats, could expand the court’s conservative majority from a relatively narrow six-to-four edge (six to five, if you include Gregory’s temporary seat) to a whopping eleven-to-four margin.

Instead, when Bush left office eight years later, the Fourth Circuit still had only six conservative (or moderate conservative) judges, and its contingent of liberal judges in lifetime seats had actually increased from four to five. Plus, there were still four vacancies on the court that Bush handed off to Barack Obama, who was thus able to transform the Fourth Circuit into a liberal bastion.

Let’s take a closer look at Bush’s dismal failure.

***

The Fourth Circuit covers the five states of Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia. Let’s start by looking at its composition in January 2001.

For ease of reference, I will refer to some particular seats by number. (The number of a seat corresponds to the order in which it was originally filled—e.g., Seat 1 was filled in 1891—and has no other significance). I will also refer to seats by state, but I emphasize again that federal law does not actually designate seats within a circuit by state.

In January 2001, the Fourth Circuit had six judges who had been appointed by Republican presidents:

Emory Widener, age 77, appointed by Richard Nixon in 1972 (Seat 4, Virginia)

Harvie Wilkinson, age 56, appointed by Ronald Reagan in 1984

William Wilkins, age 58, appointed by Ronald Reagan in 1986 (Seat 11, South Carolina)

Paul Niemeyer, age 59, appointed by George H.W. Bush in 1990

Michael Luttig, age 46, appointed by George H.W. Bush in 1991 (Seat 13, Virginia)

Karen Williams, age 49, appointed by George H.W. Bush in 1992

It had four judges whom Bill Clinton had appointed to lifetime seats over the previous eight years: Blane Michael, Diana Motz, William Traxler, and Robert King.

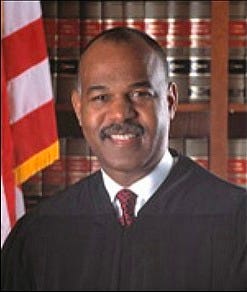

It had Clinton recess appointee Roger Gregory (Seat 15, Virginia).

And it had four vacancies: Seat 7 (North Carolina), Seat 8 (Maryland), Seat 10 (North Carolina), and Seat 12 (South Carolina).

***

In his first term, Bush succeeded in filling two of the four vacancies: Dennis Shedd to Seat 12 in 2002 and Allyson Duncan to Seat 10 in 2003.

Let’s look, in rough chronological order, at the fate of six other seats: Roger Gregory’s seat, the two other vacancies that Bush inherited, and the three other seats that would be vacated by Republican appointees.

Seat 15 (Virginia): Hindsight confirms what was clear to astute observers at the time: Bush’s appointment of Roger Gregory to a lifetime seat in 2001—a decision pressed on him by rookie Virginia senator George Allen—was a terrible blunder. I’ve addressed that decision in detail and won’t repeat it here. For present purposes, it suffices to note that Bush gave up the opportunity to appoint a conservative judge to Seat 15 and instead entrenched a very liberal judge in that seat.

Seat 7 (North Carolina): Republican senator Jesse Helms obstructed Bill Clinton from filling this North Carolina seat when it became open in 1994, and Democratic senator John Edwards returned the favor when Bush nominated Helms protégé Terrence Boyle to the seat in 2001. Even after Republican senator Richard Burr took Edwards’s seat in 2005, Senate Republicans did not use their large majority in 2005 and 2006 to confirm Boyle’s nomination. (See my fuller account.) When Bush withdrew Boyle’s nomination after Democrats won control of the Senate in the 2006 elections, he nominated Robert Conrad to the seat, but Democrats prevented any action on Conrad’s nomination. So this seat remained vacant through Bush’s presidency.

Seat 8 (Maryland): As I’ve spelled out, Maryland’s Democratic senators used their blue-slip power to deter Bush from nominating anyone to this seat in 2001 and 2002. When Bush tried to shift the seat to Virginia, their filibuster threat defeated his effort. Bush failed to find a nominee who would win their support, and this seat also remained vacant through his presidency.

Seat 4 (Virginia): In 2001, Emory Widener announced his intention to take senior status upon the confirmation of his successor. It wasn’t until September 2003 that Bush nominated Department of Defense general counsel William J. Haynes II to the seat. The Judiciary Committee, with only three Democrats voting no, favorably reported Haynes’s nomination to the full Senate in March 2004. But the eruption of controversy over horrific abuses at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq gave Democrats an excuse to stall his confirmation. As Benjamin Wittes explained in a New Republic essay, Haynes acted “very admirably” in opposing the military’s use of highly coercive interrogation techniques, including waterboarding, but somehow ended up getting “smeared” as a supporter of torture. When Bush renominated Haynes in 2005, he ended up getting blocked, bizarrely, by newly elected Republican senator Lindsey Graham. Why Graham would indulge the smearing of Haynes is a mystery.

Haynes withdrew his nomination after the 2006 elections gave Democrats control of the new Senate. Democrats refused to act on Bush’s subsequent nominees to the seat. Widener died in September 2007.

Seat 13 (Virginia): After being passed over for the two Supreme Court vacancies that opened up in 2005, Michael Luttig, then 51, resigned his judgeship in May 2006 to become general counsel of Boeing (an opportunity that, according to his resignation letter, arose “through sheer serendipity”). Two years later, Bush succeeded in appointing Virginia supreme court justice Steven Agee to the seat.

Agee’s replacement of Luttig meant that Seat 13 continued to be held by a conservative judge, so it might well be that Luttig’s resignation had no negative effect on the ideological composition of the court. But as I explained in my post on Robert Conrad’s nomination, Senate Patrick Leahy, the Democratic chairman of the Judiciary Committee, undercut a deal to give Conrad a hearing by substituting Agee in Conrad’s place. So it’s possible that if Luttig hadn’t resigned, Conrad would have been confirmed.

Seat 11 (South Carolina): William Wilkins announced at year-end 2006 that he would step down as chief judge and take senior status in July 2007. (He became eligible to take senior status under the Rule of 80 in March 2007.) The Democrat-controlled Senate refused to take any action on Bush’s nomination of Steven Matthews.

In sum: Bush gave Clinton’s very liberal recess appointee Roger Gregory a lifetime appointment, and he failed to fill four other vacancies, including three that existed for all or nearly all of his presidency.

***

What were the causes of Bush’s failures? I’ll cite three:

1. George Allen. In effectively forcing Bush to give Roger Gregory a lifetime appointment, Allen was trying to advance his own political interests at the expense of the quality of the Fourth Circuit.

When Allen ran for re-election in 2006, whatever goodwill he had built on issues of race was destroyed in his infamous “Macaca moment.” (See fuller discussion at end of linked post.) The media elevated Allen’s “Macaca moment” into the defining event of the campaign. Allen lost re-election by a very tiny margin, 0.39%.

Virginia had two Republican senators for the first six years of Bush’s presidency. If Allen hadn’t pushed Gregory on Bush, there would have been plenty of room to get a quality nominee confirmed in the four years from 2003 through 2006.

2. Republicans’ loss of the Senate in the 2006 elections. Republicans went into Election Day 2006 with a 55-seat majority. Although a reduction in that majority was expected, virtually no one anticipated a Democratic sweep of all of the close races.

If Republicans had retained control of the Senate in 2007 and 2008, Conrad, Haynes, and Matthews would probably have been confirmed. If Republicans had planned for the contingency of losing the Senate, they might well have confirmed Haynes and Boyle in 2006.

3. The Senate Judiciary Committee’s blue-slip policy. The committee’s blue-slip policy, embraced by chairmen of both parties, gave home-state senators a veto (or, in the case of Orrin Hatch as chairman, a near veto) over nominations to appellate seats in their states. Senators of both parties benefited from that policy, and there was no prospect that any chairman would abandon it. It would take another decade or so of escalation in the judicial-confirmation wars before the blue slip on appellate nominations would be demoted.

Without meaning to suggest that President Bush could have done anything to make the blue-slip disappear, I think it’s nonetheless instructive to observe how great an obstacle it was. Consider what would likely have happened if the robust blue-slip policy did not exist:

George Allen would have had no leverage to insist that Bush nominate Roger Gregory.

Terrence Boyle would probably have been confirmed after Republicans took control of the Senate in 2003.

Bush would have nominated someone (probably Peter Keisler) for Seat 8 in Maryland in 2001, and the Senate would have confirmed that nominee by 2004.

***

As we shall see, Barack Obama in his first two years would fill all four Fourth Circuit vacancies that he inherited, and in 2011 he would also replace Karen Williams. He would thus establish a dominant (ten-to-five) liberal majority on the once-conservative court.

Good writing, good substance, good lessons.

Something like the blue slip is good. How have Republicans used it ? But it should not be an absolute veto, just an occasionally used veto.

the blue slip policy needs to go