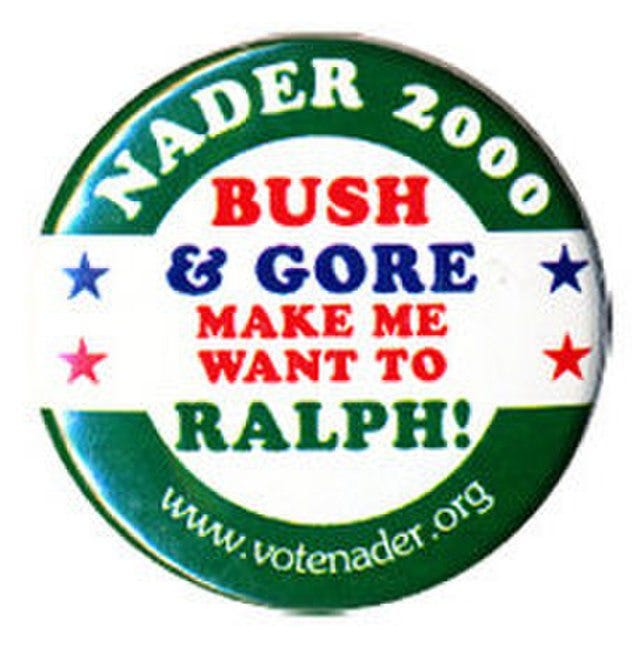

Did Breyer Nomination Cost Al Gore the 2000 Presidential Election?

Ralph Nader blasts Stephen Breyer as "extremist" supporter of "corporate power"

Stephen Breyer’s Supreme Court nomination had a fairly easy path to confirmation, but the path wasn’t celebratory. Rather than unify the Democratic party, the nomination exposed and exacerbated differences among its factions.

Ralph Nader testified vehemently against Breyer at his 1994 confirmation hearing and, more than six years later and just days before the 2000 presidential election, was still complaining about Breyer. There is thus ample reason to suspect that Bill Clinton’s nomination of Breyer spurred Nader’s fateful decision to run for president, first in 1996 and then again in 2000. If so, the Breyer nomination had a greater impact on a presidential election than any other Supreme Court nomination in American history ever did.

* * *

Liberals weren’t just angry that Bill Clinton had been cowed by my boss Senator Orrin Hatch into abandoning his plans to nominate Bruce Babbitt to the Supreme Court. Although many of them liked Stephen Breyer and respected his intellect, they saw his nomination as a betrayal of Clinton’s promise to select “someone with a big heart,” “someone of genuine stature and largeness of ability and spirit.”

Clinton had made clear that he wanted to nominate a liberal statesman in the mold of New York governor Mario Cuomo or Senate majority leader George Mitchell. Babbitt, a former Arizona governor, current Secretary of Interior, and favorite of environmentalists, fit the bill. But Clinton ended up picking a federal appellate judge best known for his technocratic expertise in regulation and antitrust.

Two weeks after Clinton announced Breyer’s nomination, the Ninth Circuit’s liberal lion Stephen Reinhardt roared his disapproval. In a remarkable open letter to Breyer published in the Los Angeles Times, Reinhardt cast his anger with Clinton in the form of a “personal appeal” to Breyer to “re-examine your judicial philosophy” and to change the sort of jurist he had been:

You can be [i.e., remain] cold, purely intellectual and wholly technical, or you can become what the President said he was looking for--a justice who is compassionate, who has a big heart. [Boldface added.]

Reinhardt didn’t conceal that he was also disappointed with Clinton’s appointment of Ruth Bader Ginsburg in 1993:

The sad truth is that you are not only succeeding Harry Blackmun. You are the only potential successor to William Brennan, Thurgood Marshall, Earl Warren, William O. Douglas and the whole line of humanitarian justices who understood the importance of compassion and the need to do justice, not just administer law. There are lots of able technicians who understand law. The nation, however, is entitled to at least one justice with vision, with breadth, with idealism, with--to say the word despised in the Clinton Administration--a liberal philosophy and an expansive approach to jurisprudence. [Boldface added; italics in original.]

* * *

As I read through Breyer’s hundreds of First Circuit opinions and his many law-review articles, I could see why Reinhardt found Breyer objectionable. But I had a much more favorable impression of Breyer’s qualities. Breyer was indeed coolly intellectual: he displayed the judicial virtue of dispassion, not compassion. He applied his brilliant and broad-ranging intellect to a variety of problems. His pragmatic approach to interpreting legal texts departed from the twin principles of originalism and textualism that Senator Hatch and I favored, and was sufficiently malleable to achieve whatever Breyer wanted, but Breyer had given few if any signs of being a wild-eyed activist like Reinhardt.

Breyer also contrasted in an interesting way with Ginsburg. In an essay on Tolstoy, Isaiah Berlin famously drew on an ancient Greek saying—“The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing”—to identify two categories of thinkers. Hedgehogs have “a single, universal, organising principle in terms of which alone all that they are and say has significance.” They seek to fit everything into “one unchanging, all-embracing, … at times fanatical, unitary inner vision.” Foxes, by contrast, “pursue many ends, often unrelated and even contradictory, connected, if at all, only in some de facto way, for some psychological or physiological cause, related to no moral or aesthetic principle…. [T]heir thought is scattered or diffused, moving on many levels, seizing upon the essence of a vast variety of experiences and objects for what they are in themselves.”

Breyer was a fox, interested in all sorts of arcane policy matters and brimming with insights, even as his thoughts sometimes seemed inchoate and undisciplined. Ginsburg was a hedgehog, who knew the “one big thing” of women’s equality and who rigidly applied that concept, even when it led to ridiculous proposals (e.g., abolishing Mother’s Day). I won’t take a stand on foxes versus hedgehogs more generally, but I did find Breyer’s writings far more interesting than Ginsburg’s.

* * *

Breyer’s nomination was unlikely ever to have any populist appeal. On top of his mien of absent-minded professor, Breyer had married into the British aristocracy—his wife Joanna was the daughter of John Hare, 1st Viscount Blakenham, a prominent conservative politician—and had the wealth (as well as the unusual accent) to show it. As the New York Times reported, Breyer’s Senate questionnaire response disclosed that he had a net worth of $8.5 million—a sum even more stratospheric three decades ago, before the Internet boom, than it is now—and four residences, including one in London (co-owned with his mother-in-law, the daughter of the 2nd Viscount Cowdray) and “a vacation home on St. Kitts in the Caribbean.”

Breyer’s Senate questionnaire response also revealed that he was an investor in a Lloyd’s of London insurance syndicate that remained liable for potentially massive losses in lawsuits. As an investor in a Lloyd’s syndicate, Breyer’s liability was not limited to the amount of his investment. Rather, he had unlimited liability for his proportionate share of the syndicate’s losses. Such an investment, the New York Times article noted, had proven to be “highly risky”: many investors “were bankrupted after they had insured companies against environmental cleanup costs and damages resulting from lawsuits involving asbestos, both of which generated huge, huge liabilities.”

* * *

At Breyer’s confirmation hearing in mid-July 1994, liberal Democratic senator Howard Metzenbaum was in as sour a mood as he was on the day that Clinton announced Breyer’s nomination. Objecting that Breyer “seem[ed] to see antitrust laws in terms of abstract economics,” Metzenbaum complained in particular that Breyer “almost always vote[d] against the very people the antitrust laws are in place to protect”:

You seem to see antitrust laws in terms of abstract economics. And it seems that theories of economic efficiency displayed in complicated charts … and graphs replace individual justice for small businesses and consumers.

Metzenbaum also challenged Breyer’s failure to recuse himself from “a case that reduces polluters’ and their insurance companies’ liability for cleaning up hazardous waste at a time when your investment at Lloyd’s of London included environmental liability insurance policies.”

Resigned to Breyer’s confirmation, Metzenbaum expressed his hope that “when you get on the Supreme Court … maybe the milk of human kindness will run through you and you will not be so technical.”

Although they typically receive little attention, panels of witnesses offer the Judiciary Committee their testimony after the nominee is done. Consumer activist Ralph Nader testified furiously against Breyer’s nomination. Nader charged that Breyer had displayed a priority for the “conservation of existing power alignments” and that his “record on antitrust is extraordinarily one-sided.” Nader concluded:

[A] nominee such as Judge Breyer, who is insensitive to the laws’ needs to discipline the excesses and concentrations of corporate power, a nominee who rests his proposals on erroneous reality, factual error and fantasy, and, above all, a nominee who rejects the efficacy of ever-improving democratic participation by the people in making these agencies of Government work better is neither pragmatic, neither realistic, nor moderate. He is extremist. He is ridden with fantasy, and he is insensitive on the ground to the health and safety needs of the American people, and his nomination should be rejected on those grounds alone.

* * *

On July 29, 1994, the Senate confirmed Breyer’s nomination by a vote of 87 to 9, with the nine negative votes coming from Republicans. But the fact that no Democratic senator voted against Breyer does not mean that his nomination energized or unified the national party. The path of least resistance for a senator is usually to support a Supreme Court nomination made by a president of the senator’s party.

Senator Metzenbaum ended up voting for Breyer, but he said that he did so “with serious reservations and a heavy heart…. [I]t is not a vote that will make me particularly proud.” In a slap at Bill Clinton, Metzenbaum asserted that Breyer’s record “has not been impressive for a judge who is supposed to have a big heart.”

In a development that no one would have expected at the outset of the process, Senator Richard Lugar, a mild-mannered moderate from Indiana, led the opposition to Breyer. Lugar charged that Breyer was “trapped in a troubled Lloyd’s of London syndicate from which he is unlikely to escape for a long period of time” and that he had “exercised extraordinarily bad judgment” in subjecting himself to unlimited liability.

A few months later, the Supreme Court’s public information office announced that Justice Breyer had purchased re-insurance (reportedly at a price of $93,000) that completely eliminated the downside risk of his Lloyd’s investment.

* * *

In 1996, Ralph Nader would make his first run for president on the Green Party platform, as he condemned the “Democratic and Republican Tweedledum-Tweedledee party.” Counterfactual speculation is perilous, but given the vehemence of Nader’s testimony at Breyer’s hearing, it’s reasonable to posit that Clinton’s nomination of Breyer helped provoke Nader’s quixotic campaign.

Nader won only 0.71% of the popular vote in 1996, but he did set the stage for his next run in 2000. I haven’t undertaken a thorough review of Nader’s campaign speeches, but I do find it striking that just eight days before the 2000 election Nader was still slamming Breyer:

Steve Breyer was considered Senator Hatch’s first choice, not just Clinton’s first choice. Senator Hatch loves him. I think he’s going to turn out to be one of the worst anti-consumer environmental regulatory justice because he’s from the old Chicago school of economics, doesn’t like regulation. [Federal News Service transcript, Oct. 30, 2000.]

In 2000, Nader won 2.74% of the national vote. More significantly, he received more than 97,000 votes in the pivotal state of Florida, which George W. Bush ended up winning by only 537 votes.

If Clinton had nominated the environmentalist Babbitt instead of the Lloyd’s insurance investor Breyer in 1994, perhaps Nader never would have launched a presidential campaign, and Al Gore would have won Florida comfortably, and been elected president, in 2000. Which president would then have made the next Supreme Court appointments, and how different would the Court be now? One can only wonder.

It is interesting to speculate who would have appointed the next Justices, had Al Gore defeated George Bush. Although in frail health, William Rehnquist did not retire, and instead, like Ruth Bader Ginsberg, died in office. Sandra Day O'Connor was partisan enough that she retired in 2005 so that a Republican would appoint her successor.

The only times in American history that the same political party won 4 or more Presidential elections in a row were 1932-1952 (FDR and Truman); 1896-1912 (McKinley, Roosevelt, and Taft); 1860-1884 (Lincoln, Grant, Hayes, and Garfield); and 1800-1828 (Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, and JQ Adams).

Given their backgrounds, both John Roberts and Samuel Alito were likely Supreme Court nominees regardless of the Republican President nominating them. So the Al Gore scenario only works if Gore defeats Bush in 2000 but is also re-elected in 2004.