Barack Obama Imperils Fifth Circuit Nomination...

... and Dianne Feinstein rescues it

As you go deeper into any judicial-confirmation battle, you encounter the incentives, constraints, and personal relationships that shape the behavior of individual senators. In Fifth Circuit nominee Leslie Southwick’s confirmation saga, Barack Obama and Dianne Feinstein each played an outsized role.

(I draw heavily in this post from Southwick’s book on his confirmation battle.)

***

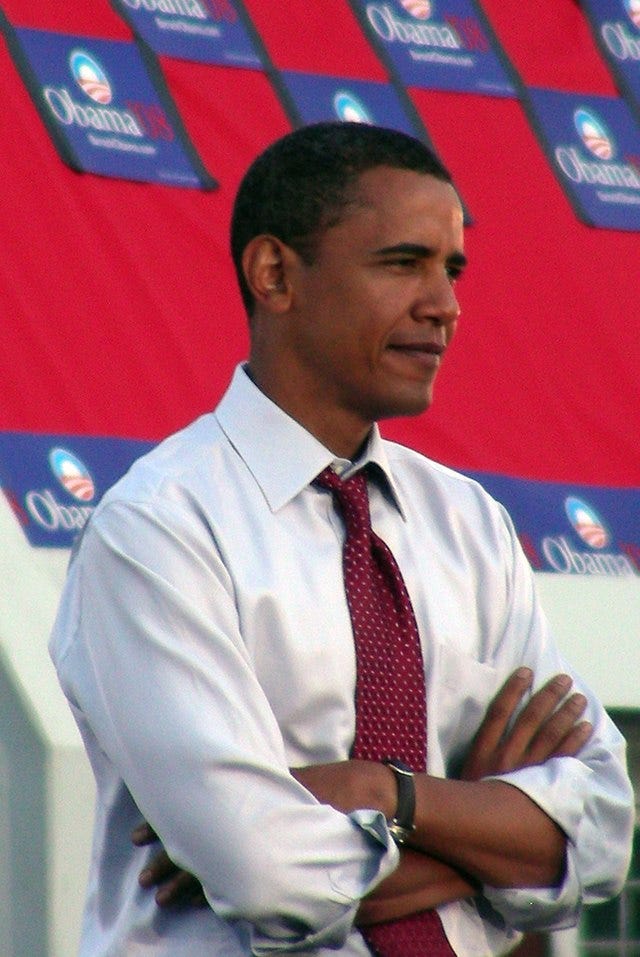

At the end of May, a first-term senator from Illinois, a fellow by the name of Barack Obama, became the first senator to declare his opposition to Southwick’s nomination. Obama wasn’t even on the Judiciary Committee, and it was strange that he would jump ahead of committee Democrats. But he had declared a few months earlier that he was running for president, and he obviously recognized that he could bolster his support from the Left by embracing its scurrilous, racially charged attack on Southwick.

Obama’s opposition to Southwick put Patrick Leahy, the Democratic chairman of the Judiciary Committee, in a bind. When George W. Bush nominated Southwick as a peace offering to Democrats, Leahy assured Mississippi’s Republican senators, Thad Cochran and Trent Lott, that Southwick would be confirmed by Memorial Day. Even after the Left attacked Southwick, Leahy told Cochran that he was “likely” to vote for Southwick and would encourage everyone else on the committee to do so. Leahy clearly recognized that the attack on Southwick was makeweight. But now he had to contend with Obama’s opposition to Southwick.

Leahy tried to persuade the White House to withdraw Southwick’s Fifth Circuit nomination, to nominate him instead to a district-court seat, and to nominate an African American to the Fifth Circuit seat. His proposal recognized that the insinuations of bigotry being leveled against Southwick were bogus: if they had any merit, it would make no sense to approve Southwick for any court, much less a trial court where a judge would have broad discretion in criminal sentencing and factfinding. The White House steadfastly rejected Leahy’s proposal.

At the same time, Leahy accommodated Cochran by agreeing not to hold a committee vote on Southwick’s nomination until Cochran thought the time was right. That meant that Senate Republicans could continue to hunt for the single Democratic vote they needed to send his nomination to the Senate floor.

***

Arlen Specter, the senior Republican on the Judiciary Committee, embraced Southwick’s cause. Specter hadn’t been able to attend Southwick’s hearing. But after reviewing the charges against Southwick, Specter declared that “there’s absolutely no reason not to confirm Judge Southwick.” Indeed, “If we can’t confirm Southwick, I don’t know anybody we can confirm.”

Specter prepared for a political battle. Two months after Southwick’s hearing, he met with conservative leaders active in judicial-confirmation fights, including yours truly. A Politico article on the meeting quoted me:

“There are folks who didn’t care squat about Southwick in the beginning who now feel he is a good man and he’s being treated unfairly,” said Ed Whelan, president of the Ethics and Public Policy Center. “Now, they feel this is the right fight to fight.”

(Ouch on my two sloppy uses of “feel” instead of “believe.”)

Southwick kindly emailed me to thank me for my blog posts that refuted the attacks on him. I replied:

As you are probably aware, there are plenty of hardened Senate staffers who are particularly appalled by the unfair treatment that you are receiving. Although there are significant challenges ahead, I remain hopeful that you will be confirmed.

***

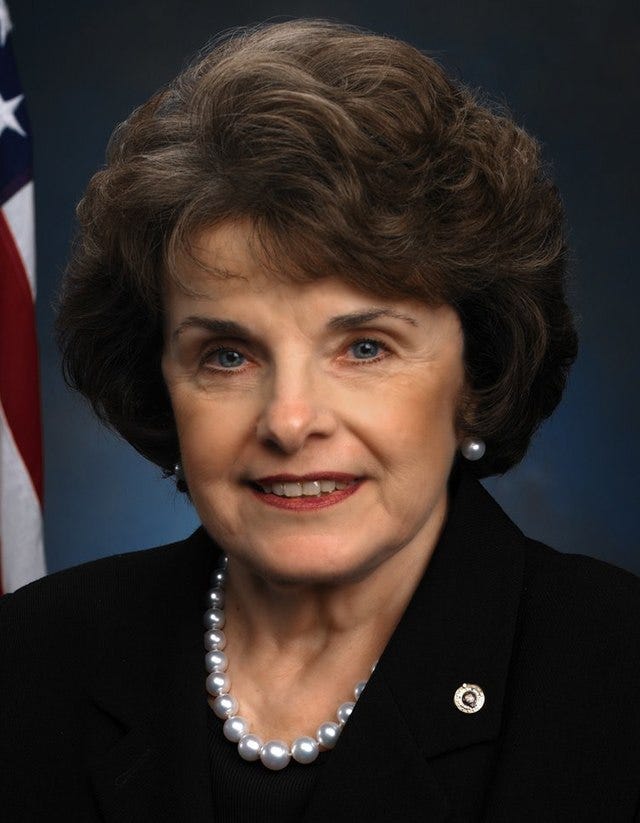

The same day that Specter met with us, Southwick met with Dianne Feinstein, a liberal Democrat from California who was a member of the Judiciary Committee. Feinstein told Southwick that she was angry at George W. Bush and the Supreme Court and that she was less likely to vote for him as a result. Southwick did not find the meeting encouraging.

But Feinstein would end up being the unlikely heroine in Southwick’s confirmation saga.

Southwick evidently made a much more favorable impression on Feinstein than he realized. Feinstein knew a race hustle when she saw it. She also trusted her own ability to take the measure of a nominee from a face-to-face meeting.

Three weeks later, when Leahy announced that the committee would vote on Southwick’s nomination, the media reported that Southwick would be defeated on a party-line vote. When Leahy privately informed Cochran that Southwick was likely to be voted out favorably, Cochran didn’t know which Democrat would provide the coveted “aye” vote. Nor did Southwick’s sherpas at the Department of Justice.

Trent Lott, it appears, had been making headway with Feinstein on Southwick’s behalf. The afternoon before the committee vote, Lott told Southwick that Feinstein wanted a letter from him. Feinstein then called Southwick and told him that she was leaning toward voting for him but that she wanted him to say that he shouldn’t have joined the opinion (discussed more fully here) that affirmed an administrative ruling that an ugly racial slur—the N-word—by a public employee did not justify the sanction of terminating her employment. Southwick told her that he could not do that. Feinstein told him that she needed a letter from him that evening acknowledging some sort of mistake.

Southwick decided that he needed to spell out for Feinstein why the opinion did not reflect an unacceptable attitude about race. In a long letter, he repeated his hearing testimony that the N-word “is the worst of all racial slurs,” and he wrote that he regretted that the opinion’s “failure to express in more depth our repugnance of the use of this phrase has now led to an impression that we did not approach this case with sufficient gravity and understanding of the impact of this word.”

Southwick faxed the letter to Feinstein at 10 p.m.

***

On August 2, 2007, Senator Feinstein provided the decisive vote to report Southwick’s nomination to the Senate floor. It would take nearly three more months for the Senate to confirm Southwick’s nomination. On October 24, a Democratic effort to filibuster his nomination failed, as a cloture motion passed by a vote of 62 to 35 (two more votes than it needed). Southwick was then confirmed by a vote of 59 to 38.

***

After the confirmation vote, a celebration took place in the Judiciary Committee hearing room. I was pleased to attend and to meet Southwick. In addition to several Republican senators, Feinstein took part in the celebration and received a hero’s welcome.

I thanked Feinstein for her courage and used the opportunity to tell her that there was another pending nominee who had been unfairly abused. I urged her to help him out. Who’s that?, she asked. D.C. Circuit nominee Peter Keisler, I replied. A look of dread crossed her face, and I realized that my request would go nowhere.

***

In his nearly two decades on the Fifth Circuit, Leslie Southwick has been very much in the center of the court. I’ve been asked whether I’m disappointed to have worked hard to confirm him. Not one bit.

As I wrote two days before his confirmation:

I haven’t reviewed Judge Southwick’s judicial record beyond the cases that the Left has misrepresented. Folks like me who are making the case for his confirmation are doing so out of a conviction that the lies of the Left should not defeat a good and decent and fully qualified nominee, not from any belief (much less a well-founded belief) that Judge Southwick will be a champion of conservative jurisprudential principles.

I met with Specter on behalf of the RNLA on the Southwick nomination. We all pushed hard and were grateful for Feinstein's support (not the last time if I recall). When I finally appeared before him years later I get my head handed to me. Still, no regrets!

Terrific and important history.