Antonin Scalia on What Makes an American

I’m on vacation in Italy and am taking a break from my usual Confirmation Tales fare. As a fitting substitute, I am passing along these excerpts from a speech that Justice Antonin Scalia gave to the National Italian American Foundation in October 1986, the month after he became the first Italian American to sit on the Supreme Court.

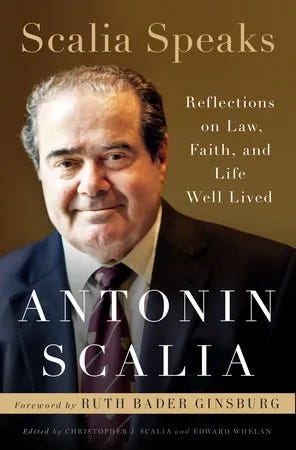

I draw the speech from Scalia Speaks: Reflections on Law, Faith, and Life Well Lived, the New York Times bestselling collection of Scalia’s speeches that I had the privilege of editing with Scalia’s son Christopher. We titled the speech “What Makes an American.”

* * *

My fellow Italian Americans:

I want to say a few words this evening about why we are proud of our Italian heritage—and about why that pride makes us no less than 100 percent Americans.

The Italian immigrants who came to this country possessed, it seems to me, four characteristics in a particularly high degree—characteristics that continue to be displayed, by and large, by their descendants.

First, a capacity for hard work— whether on the lines of the railroads whose construction brought many of them here, or in the machine shops and garment factories of the industrial East, or in the fisheries and vineyards of California.

Second, a love of family. The closeness of the Italian family is legendary—it is one of our great inheritances.

Third, a love of the church. Italian American priests and Italian American parishioners have—with a good deal of help, it must be acknowledged, from our Irish coreligionists in the East and Hispanic Americans in the West—made Roman Catholicism one of the major religions in a country where it began as a tiny minority.

And fourth, perhaps arising from the first three—the product of hard work, a secure family environment and a confident knowledge of one's place within God's scheme of things—a love of the simple physical pleasures of human existence: good music, good food, and good—or even pretty good—wine.

We have shared those qualities with our fellow Americans—as they have shared the particular strengths of their heritages with us. And the product is the diverse and yet strangely cohesive society called America. It is a remarkable but I think demonstrable phenomenon that our attachment to and affection for our particular heritage does not drive our society apart, but helps to bind it together. Like an intricate tapestry, the fabric of our society is made up of many different threads that run in different directions, but all meet one another to form the whole.

The common bond I have with those who share my Italian ancestry prevents me from readily being drawn into enmity with those people on the basis of, for example, politics. If I were, for example, a Republican, I could not think too ill of Democrats—because, after all, Pete Rodino is a Democrat and he's a paisan. And of course we all have loyalties based on factors other than our ethnic heritage that bind us together with other Americans—we go to the same church as they, or belong to the same union, or went to the same college. It is these intersecting loyalties to small segments of the society that bind the society together.

So I say you can be proud of your Italian heritage—as the Irish can of theirs, and the Jews of theirs—without feeling any less than 100 percent American because of that.

While taking pride in what we have brought to America, we should not fail to be grateful for what America has given to us. It has given us, first and foremost, a toleration of how different we were when we first came to these shores. What makes an American, it has told us, is not the name or the blood or even the place of birth, but the belief in the principles of freedom and equality that this country stands for.

There have, to be sure, been instances and periods of discrimination against Italian Americans, just as there have been against all other new arrivals. But that was the aberration, the departure from the norm, the failure to live up to the principles on which this Republic was founded.

If you do not believe that, you need look no further than the actions of the greatest American of them all, the Father of our Country, George Washington. During his first term in office as president, Washington wrote a letter that is a model of Americanism, addressed to the Hebrew Congregation of Newport, Rhode Island. This blue-blooded, aristocratic Virginian assured that small community that his administration, his country, would brook no discrimination against that small and politically impotent community. And that the children of Abraham, as he put it, were welcome in this country, to live in peace and never to have fear.

* * *

Ciao!