Clinton’s Tortuous 86-Day Selection Process

Repeatedly just 'two to three weeks away' from a decision

Justice Byron White informed the White House on March 20, 1993, that he would retire at the end of the Court’s term. It was an extraordinary 86 days later, on June 14, that President Clinton announced that he would nominate D.C. Circuit judge Ruth Bader Ginsburg to fill White’s seat.

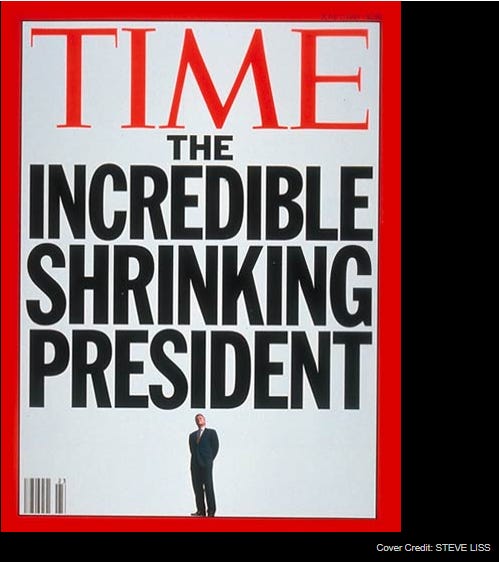

Clinton’s selection process was tortuous. One reason is that Clinton had gotten off to a terrible start as president. With a cover that ridiculed him as “The Incredible Shrinking President,” Time magazine that spring observed that his presidency “has been beset since its inception by miscalculations and self-inflicted wounds” and that his “popularity with voters continues to decline.” So the White House was especially intent on making sure that Clinton’s pick would be well received.

But Clinton’s own vacillations were the primary cause of delay.

On March 20, the day of White’s retirement announcement, the New York Times reported:

The vacancy presents a tantalizing opportunity for President Clinton, although one that could easily become entangled in the sort of ethnic and sexual politics that prolonged his efforts to staff the Cabinet. Saying today that he will promptly move to fill the seat, Mr. Clinton steered clear of ideology and specifics and listed experience, judgment and “a big heart” among his criteria.

Two weeks later, the White House abandoned its goal of a prompt nomination. According to the New York Times on April 6, Clinton himself was “far more involved” than recent presidents had been in the groundwork of selecting a nominee and wanted to extend the search beyond lower-court judges. The article identified three candidates: New York governor Mario Cuomo, New York’s chief judge Judith Kaye, and D.C. Circuit judge Patricia Wald. The selection process was moving very slowly, and White House staffers tried to spin that slowness as a virtue:

The White House has decided to wait until at least May or June at the earliest to announce its choice to succeed Justice White on the theory that a replacement is not needed before the Court reconvenes in October. It also calculates that politically it would be better to keep short the amount of time between nomination and confirmation to reduce the likelihood of a campaign to block confirmation.

Just two days later, Cuomo withdrew as a candidate. White House officials revealed that other contenders included First Circuit judge Stephen Breyer, district judge José Cabranes, Second Circuit judge Amalya Kearse, and Wald. Clinton was now said to be “still two to three weeks away from announcing a selection.”

A full month later, on May 9, the New York Times again reported that Clinton was expected to announce his nominee “within the next two or three weeks.” Why so much delay? “[I]f there is a single reason why this search has taken significantly longer than previous Supreme Court searches, it is because it has largely been playing out in Mr. Clinton's head.” The “list of candidates,” the article noted, “has been growing and shrinking almost daily” since White announced his retirement.

For the first time, the New York Times included Ruth Bader Ginsburg in its list of seven candidates “under the most serious consideration.” Clinton would be inclined to pick a Democratic senator as his nominee, but “Democrats' slim [!!] majority in the Senate makes it politically unpalatable to do anything that would erode the party's control of Congress.” (The Democrats held a 57-43 majority.)

The very next day, a column by Anthony Lewis lamented that some women’s groups opposed Ginsburg because they were angered by a speech she had recently given that faulted the Court for going too far too fast in Roe v. Wade.

In late May, White House officials told the New York Times that they had “narrowed their search … to two Federal appellate judges from New England,” Breyer and Second Circuit judge Jon Newman, and that they expected a decision from Clinton by the following week.

Then on June 8, Secretary of the Interior (and former Arizona governor) Bruce Babbitt suddenly emerged as the top contender. Babbitt’s spokesman confidently declared, “I think it’s going to happen.” A New York Times article identified only two other contenders, Breyer and Sixth Circuit judge Gilbert Merritt. The article noted that both Senator Hatch and Senate minority leader Bob Dole had spoken out in favor of Breyer. It also mockingly observed:

For nearly three weeks, White House spokesmen and the President have said that the nomination was imminent, but each time it has been delayed for various reasons: some candidates high on Mr. Clinton's list dropped out, unexpected political crises arose and some names that were floated generated quick opposition.

The very next day, the New York Times reported that Senator Hatch declared Babbitt to be “unacceptable” as a “political figure on the bench who might substitute his … visceral or personal beliefs for the law.”

On June 14, Clinton finally announced his nomination of Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

This narrative suggests a few lessons that we will see again:

1. Each president brings his own characteristics of decision-making to the process of nominating a justice. Different characteristics have their offsetting advantages and disadvantages. Clinton was very much at one extreme in the extent of his personal involvement in assessing the candidates and their records and in his inability to reach closure on his decision.

2. It’s easy for the selection process to take much longer than it should. Clinton had the luxury of a lot of time, so his slow pace didn’t hurt him much. (As I will discuss later, Obama’s effort to fill the Scalia vacancy in 2016 would have been much more likely to succeed if he had selected a nominee within a week of Scalia’s death rather than 31 days later.)

3. Short-term political considerations (e.g., the White House’s fear of eroding its Senate majority) can play a seemingly disproportionate role in the process. There is a temporal mismatch between the desire of a president and White House staffers to secure a political victory and the decades-long impact that a justice might have on the Court.

4. A White House doesn’t do itself or potential candidates any favors by leaking their names. Leaks give opponents an opportunity to concentrate their fire. Yes, it’s useful to know in advance who might not be happy with a nominee, but there are better ways to find that out than by triggering responses to news articles.

5. No matter how intent a president is on selecting a politician with a “big heart” and a breadth of real-world experience outside what some deride as the “judicial monastery,” there will always be various judges who will be viewed as safer and higher-quality picks. The longer the process goes, the less likely it is that a president will try something daring. (The last politician to be appointed to the Court was Earl Warren seven decades ago.)