1994 Republican Senate Candidates Fight on Judges

Unlearning the wrong lesson from Judge Bork's defeat

When Bill Clinton became president in January 1993, he surely expected to have a Democratic Congress throughout his four-year term. Democrats enjoyed a 57-43 margin in the Senate and an 80+ margin in the House of Representatives.

The Senate margin declined to a still very comfortable 56 to 44 in June 1993, when Kay Bailey Hutchison defeated Bob Krueger to take the second Texas seat. (Krueger was the interim successor to Lloyd Bentsen, who had resigned to become Clinton’s Treasury Secretary.) As the Washington Post reported in September 1993, the Senate map in the November 1994 elections was very favorable to Republicans: “Democrats will be defending nearly two-thirds of the seats at stake, 21 seats as opposed to 13 for the Republicans.” But:

The bad news for the Republicans is they would need to hold all their seats and pick up seven Democratic seats to take control of the Senate, an unlikely scenario.

"If you look at it realistically, chances of picking up seven seats and gaining control of the Senate are relatively small," Sen. Phil Gramm (Tex.), chairman of the GOP senatorial campaign committee, said recently.

In the fall of 1994, Republican candidates for Senate and House seats campaigned on the theme that Clinton had betrayed his promise to be a centrist. I was surprised and very pleased to discover that his appointments of liberal judicial activists Rosemary Barkett and Lee Sarokin to federal appellate seats were widely used as evidence of his betrayal, particularly on the topic of crime.

As we have seen, in Tennessee, where liberal Jim Sasser had twice previously breezed to re-election, political novice Bill Frist made Sasser’s support of bad judges a prominent part of his campaign. He faulted Sasser for recommending Jimmy Carter’s appointment of a federal district judge in Nashville, John T. Nixon, who Frist said had “repeatedly hamstrung the courts by delaying action in death penalty cases,” and he charged that Sasser’s vote for Rosemary Barkett’s nomination showed that “he still hasn’t learned his lesson.” One month before the election, Frist called on Sasser to vote against Sarokin, and Sasser saw no choice but to comply.

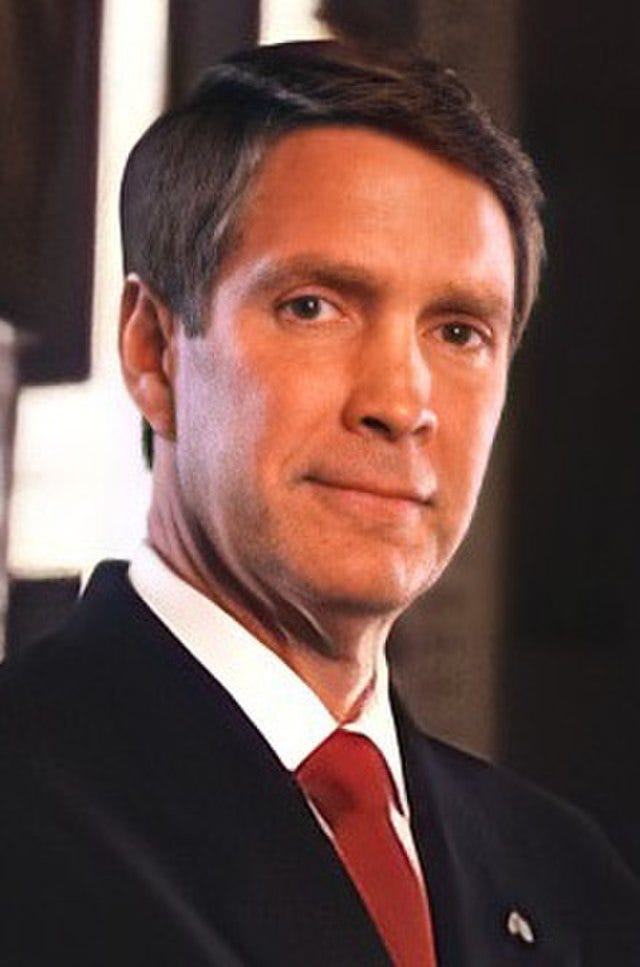

Tennessee’s other Senate seat—which Al Gore had vacated to become Vice President and which Harlan Matthews filled for two years—was also up for election. Lawyer and actor Fred Thompson ran for the open seat against longtime Democratic congressman Jim Cooper. If I recall correctly, Thompson was the first Republican candidate that I heard on the campaign trail (via C-Span or CNN) slamming Barkett and Sarokin.

A Nexis search three decades later can’t provide a comprehensive account of the use that Republican candidates made of the Barkett and Sarokin nominations, but ample traces remain. To cite some examples: In California, Michael Huffington ran television and newspaper ads that faulted Dianne Feinstein for voting for both. In a televised debate in Pennsylvania, Rick Santorum criticized Harris Wofford for voting to confirm Barkett: “Judge Barkett is known throughout the country as one of the most liberal judges in letting criminals out of jail and in not enforcing the law.” In Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Virginia, challengers to incumbents faulted them for their votes for Barkett and Sarokin.

To be clear: I am certainly not arguing that the Barkett and Sarokin nominations were a major factor in the 1994 Senate campaigns. Nor am I arguing that criticism of incumbents for voting for them was some sort of magic bullet for underdog challengers. (It obviously wasn’t.)

What I find striking, rather, is that Republican candidates discovered that they could score points in a political fight over liberal judges. Many Republicans had, I think, drawn from the searing defeat of Robert Bork’s Supreme Court nomination in 1987 the mistaken lesson that fighting over judges was a political loser for conservatives. They were now learning otherwise.

* * *

Election Night in 1994 was a shocker. Republicans, with a gain of 54 seats, won control of the House for the first time in decades. They also won control of the Senate by gaining eight seats, giving them a 52-48 margin. Frist, Thompson, and Santorum were among the newly elected senators. Frist trounced Sasser by 14 points, Thompson won by 22 points, and Santorum fought to a 2-1/2 point victory. (Feinstein defeated Huffington by less than two points.)

My own boss Orrin Hatch, whose advisers had urged him to play it safe during the “election cycle” of the previous two years, won election to a fourth term by a margin of more than 40 points. Hatch would become the new chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee.

The day after the election, Richard Shelby of Alabama changed his party affiliation from Democrat to Republican, so that meant that Republicans would have 53 seats in the new Senate.

Great post. It brought back memories. Richard Shelby wasn't the only Democrat-turned-Republican after the 1994 election - Colorado's Ben Nighthorse Campbell also switched.