Replacing Harry Blackmun

Clinton searches for candidate “with a big heart"

Sometimes a justice’s retirement comes as a surprise. This one didn’t.

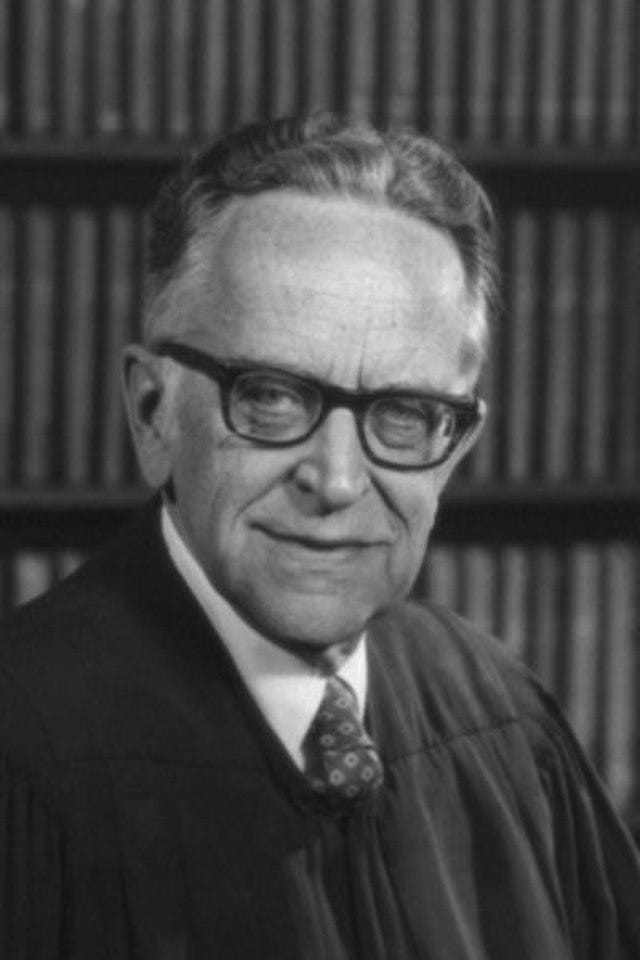

On April 6, 1994, Supreme Court justice Harry Blackmun announced that he would be retiring from the Court. Blackmun, 85 years old, had served as a justice since 1970, after just over a decade as a federal appellate judge on the Eighth Circuit. He was a dozen years older than the next oldest justice. Although he had been appointed by a Republican president, Blackmun would be glad to have Bill Clinton name his replacement, all the more so given Clinton’s explicit pro-Roe v. Wade litmus test.

Blackmun was Richard Nixon’s third pick for the Supreme Court seat that Justice Abe Fortas had vacated in a cloud of scandal in May 1969. The Senate voted down Nixon’s first nominee, Fourth Circuit judge Clement Haynsworth, by a vote of 55-45 in November 1969. The Senate had 57 Democrats and 43 Republicans, but the vote on Haynsworth was not on party lines: Amidst charges that Haynsworth was hostile to civil rights and unions, 19 Democrats, all but one (Mike Gravel of Alaska) from the South, voted for Haynsworth, and 17 Republican senators voted against their same-party president’s nominee.

Nixon’s second pick, Fifth Circuit judge Harrold Carswell, suffered a similar fate. Criticized for his level of competence as well as for his civil-rights record, Carswell elicited the famous defense of mediocrity from Senator Roman Hruska:

Even if he were mediocre, there are a lot of mediocre judges and people and lawyers. They are entitled to a little representation, aren’t they, and a little chance? We can’t have all Brandeises, Frankfurters and Cardozos.

The Senate rejected Carswell in April 1970 by a 51-45 vote. Once again, in the very different Senate of that time, when party affiliation did not so closely reflect broader ideology, the vote was not on partisan lines: 17 Democrats voted for Carswell’s nomination, and 13 Republicans voted against.

Blackmun’s confirmation process was much smoother. Nominated by Nixon one week after Carswell’s defeat, Blackmun was confirmed unanimously by the Senate less than a month later.

Raised in St. Paul, Minnesota, Blackmun was a boyhood friend of Chief Justice Warren Burger and had been Burger’s best man at his wedding. Burger had been instrumental in both of Blackmun’s judicial appointments, and the press initially labeled them the Minnesota Twins.

Blackmun is most known for his 1973 majority opinion in Roe v. Wade, an opinion that earned harsh criticism even from liberals who support a right to abortion. As one of Blackmun’s later law clerks, Edward Lazarus, who said he “loved [Blackmun] like a grandfather,” put it:

As a matter of constitutional interpretation and judicial method, Roe borders on the indefensible…. Justice Blackmun’s opinion provides essentially no reasoning in support of its holding.

In the years following Roe, Blackmun moved away from Burger and became a reliable part of the Court’s liberal wing. Perhaps that is because Blackmun, in the words of liberal legal scholar David J. Garrow, “displayed a scandalous abdication of judicial responsibility” and “ceded to his law clerks much greater control over his official work than did any of the other 15 justices from the last half-century whose papers are publicly available.”

One example: Blackmun’s clerks “were almost wholly responsible for his famous denunciation of capital punishment” in a dissent from a denial of certiorari, less than two months before he announced his retirement. One memo from a clerk to Blackmun regarding a new draft of the dissent encapsulated how Blackmun had traded roles with his law clerks: “I have not altered any of the cites,” the law clerk wrote to Blackmun. “It is therefore unnecessary for you to recheck the cites for accuracy.”

* * *

Twenty-six years, and fourteen consecutive Supreme Court nominations by Republican presidents, had passed between LBJ’s appointment of Thurgood Marshall in 1967 and Bill Clinton’s appointment of Ruth Bader Ginsburg in 1993. Blackmun’s retirement meant that Clinton would now be able to make his second pick just a year after his first.

At a White House ceremony on April 6 with Blackmun, Clinton promised to nominate someone “of genuine stature and largeness of ability and spirit.” That promise echoed his vow the previous year to select “someone with a big heart.”

Blackmun disclosed that he had informed the White House of his plans to retire “some months ago,” so one might have thought that Clinton would already be on the verge of making his pick. The Post reported that the White House was “determined to avoid a repeat of [the previous] year’s drawn-out process”—an extraordinary 86 days from vacancy to announcement of nomination. The White House “has been assembling the names of possible replacements for months” and planned to “move with dispatch.”

White House officials gave the Washington Post and the New York Times the same list of leading candidates to replace Blackmun: Senate Democratic leader George Mitchell; federal district judge José Cabranes; Interior Secretary (and former Arizona governor) Bruce Babbitt; Solicitor General Drew Days; and Clinton’s fellow Arkansan, Eighth Circuit judge Richard Arnold.

Conspicuously missing from the White House list was the previous year’s runner-up to Ginsburg, First Circuit judge Stephen Breyer. But the omission of Breyer was not surprising.

Clinton had interviewed Breyer in 1993 for Justice Byron White’s vacancy. But (as Jeffrey Toobin reported) the interview with the wonky former law professor and regulatory expert “went badly.” Clinton told his staff that Breyer, far from meeting his “big heart” criterion, seemed “heartless”:

I don’t see enough humanity. I want a judge with soul.

According to Toobin, Clinton’s staff nonetheless managed to persuade him near midnight that same day to nominate Breyer for White’s seat. But Clinton quickly changed his mind the very next morning when concerns arose that Breyer might have tax problems over his household help—an issue that had plagued Clinton’s early nominations.

A year later, Breyer seemed to be out of the running for the Blackmun vacancy.